Lion tamer, U.S. president, inner-city high school teacher, air traffic controller. To this list of stressful jobs, add one more: manager . The headline on a tech industry blog suggests, “First, Kill All the Managers.”1 Another blog, entitled “I Don’t Want to Be a Manager,” says, “Middle management has become a euphemism for meddling, ineffectual supervision and frustrating career coma.”2 An article in Business Insider begins, “To many people, middle management is a punch line – the physical embodiment of bureaucracy.”3 Is this the inevitable fate of people perched on the middle rungs of the organizational ladder? Have modern organizations evolved beyond the bureaucratic organizational form? Has hierarchy (and, consequently, supervision) become obsolete?

Not So Fast

Before declaring the manager job dead, we should check with employees. Data from Towers Watson’s 2012 Global Workforce Study show that the immediate manager influences three of the top-five drivers of employee engagement. In addition to direct effect through actions like treating people with respect and encouraging new ideas, the way managers help people set personally and organizationally meaningful goals and deal with stress at work have a profound impact on employee engagement. A 2010 Economist Intelligence Unit report found that the motivational ability of the immediate line manager was the single strongest contributor to employee motivation.4 Clearly, the people doing the work don’t think managers are irrelevant. The former CEO of a large international staffing company summarized it well: “At the extremes – really bad and really good – executive leadership probably makes some difference in the lives of individual employees. But, for everything in between, the first-line manager has much more influence over whether people feel inspired or demoralized on the job.”

All of this suggests that it’s premature to conclude that organizations don’t need managers. But, it does raise a legitimate question: What kind of managers do they need? In answering this question, we encounter the first of several paradoxes associated with the manager role. In this 21st century world of infinite interpersonal connectivity and vast information availability, they want more personal contact. In the words of management expert Marcus Buckingham, the immediate manager’s challenge is to “turn one person’s particular talent into performance. Managers will succeed only when they can identify and deploy the differences among people, challenging each employee to excel in his or her own way.”5 Using insight into each individual’s abilities, motivations and aspirations, managers must help people achieve that talent-to-performance transformation one person at a time.

Dimensions of Manager Performance

The best managers apply their one-person-at-a-time approach on two different dimensions of performance. Management guru Peter Senge has famously said that an organization’s only sustainable competitive advantage comes from the ability to learn faster than the competition. Good managers contribute to organizational learning by connecting individual employees with training, coaching and then giving frequent feedback. The best managers also combine their focus on development with an emphasis on creating a trusting environment. Not only do the best managers act with integrity, but they also display humility, intellectual honesty, interpersonal sensitivity and behavioral consistency, which generate trust. Together, development efforts and trust-building constitute what we refer to as a manager’s growth focus.

Balancing the emphasis on trust and growth is a performance focus. Effective managers boost performance by helping employees craft jobs that have ample energizing elements (such as interesting work and fulfilling team relationships) and the right level of challenge (neither too much, nor too little) with the fewest possible performance obstacles (role ambiguity and organizational politics, for instance). To reward employees for success, top-performing managers draw from the full spectrum of financial, non-financial, intrinsic, and extrinsic rewards to sculpt individualized deals with employees. They creatively use such elements as recognition, learning opportunities, project assignments and access to other leaders. Astute managers know the difference between merely administering pay and benefit systems and delivering a true employee value proposition.

In addition to their dual concentration on employee growth and performance, the best managers also energize change by envisioning, planning for, and creating the future. Sometimes, this requires responding to change that is imposed and unavoidable – reorganization, strategic redirection or downsizing, for example. In other cases, innovation and creativity may spark the change as people develop new offerings or find better ways to work.

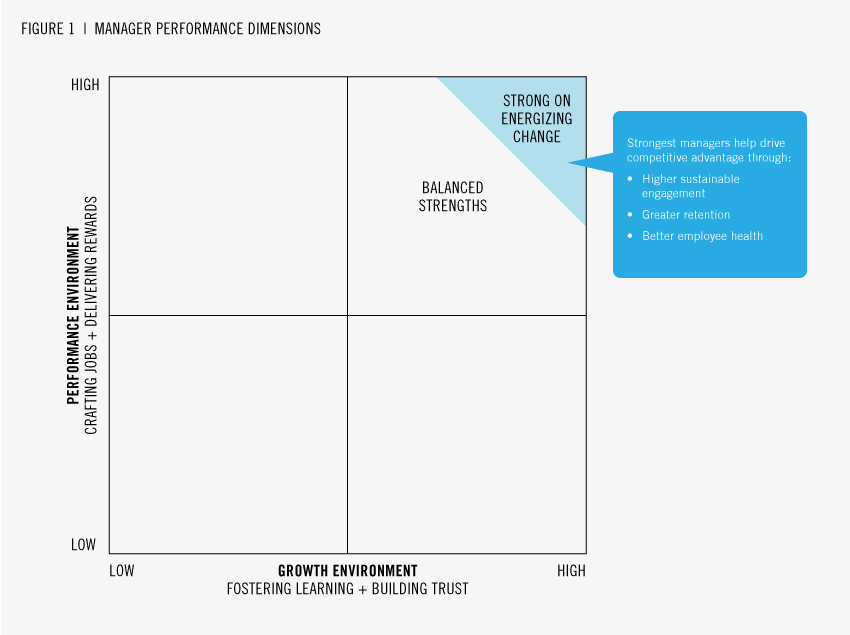

In Figure 1, the vertical axis represents success at focusing employees’ energies on achieving high individual and unit performance. The horizontal axis incorporates the manager growth focus, integrating the trust building and people development aspects of the manager role. Managers who balance these dimensions fall into the upper-right quadrant of the graphic. But, those who also possess the competencies required to energize change effectively occupy the upper corner of that quadrant. These are the great managers whose people are productive, growing and creative. They make up about 15 percent of the manager population globally. The departments they lead don’t just perform today’s work well, they also anticipate tomorrow’s work, and have the capabilities and resiliency to actually begin doing it.

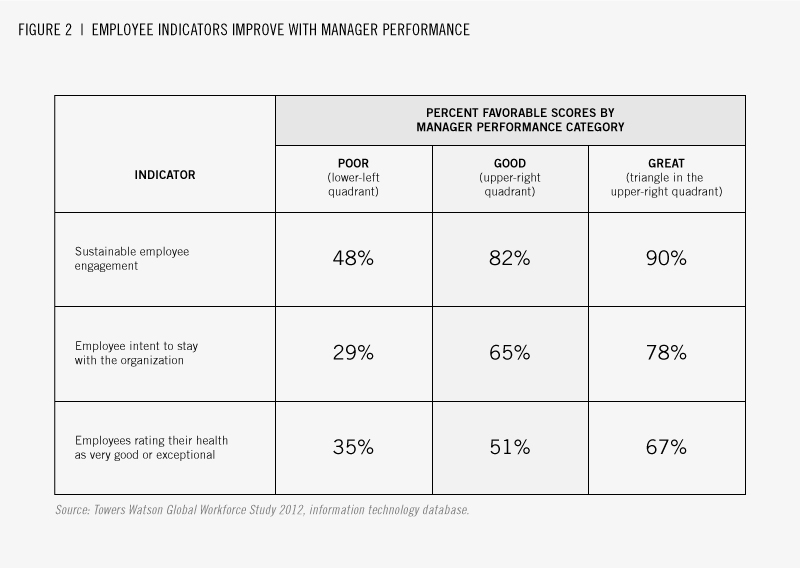

When managers perform well on these dimensions, employees thrive and organizations prosper. Figure 2 shows the results in three areas: employee engagement, employee intent to stay with the organization, and self-reported employee health. The data pertain specifically to the information technology function, an area where things move particularly quickly and managers face complex interpersonal and technical challenges.

Each of these factors has economic implications: greater individual worker productivity, lower turnover and replacement costs, and reduced absenteeism and presenters.

More Paradoxes

But, it is the 21st century, and this isn’t your father’s management job. Having defined the basic facets of performance, we must now ask how managers go about executing in these areas. What do the best manager/leaders do, as they attend to their growth and performance responsibilities that differentiate them from lower-contributing peers? Herein we find more paradoxes.

Managing the environment, not the people

The best people managers don’t concentrate on managing people. Instead, they create an environment in which people thrive. No employee we’ve ever surveyed or spoken to has said, “I want my manager to manage me more closely.” Many have told us, however, that they want managers to provide the resources and context required for success, and then get out of the way. Providing this kind of support means that:

- Major obstacles to productivity and performance have been removed, or at least mitigated; these include lack of information, political pressures and unclear roles;

- Physical work conditions are comfortable and conducive to high productivity;

- All the resources (physical, financial and informational) required to do various jobs are readily available;

- Safety on the job is never compromised, even at the expense of output; and,

- Unit staffing is sufficient to ensure that the workload is manageable and spread evenly and fairly.

When managers deliver these requirements, they boost the effect of employee engagement on individual and enterprise performance.

We worked with a technology company to help restructure the roles of middle managers so they could spend more time creating a productive environment. We began by asking managers how much of their time should be dedicated to constructing the work situations that would permit people to be most successful. They told us that, ideally, activities associated with the growth, performance, and change dimensions should account for more than 75 percent of their time – almost four days per week. At the time of our initial analysis, these activities took up about half this much of the typical manager’s week. This organization is full of smart, motivated, confident people. They want their managers to help them learn, improve how work gets done and deal with the constant change that characterizes the technology sector. They don’t need to be managed, but their work does, with help from their immediate managers.

Micromanaging – but not in the usual way

The conventional definition of micromanagement refers to inappropriately close observation and control of a subordinate’s work by a manager. There’s another definition, however: expanded availability that allows managers to be immediately available when needed – present physically, intellectually and emotionally to coach, advise and inform when it’s most useful. When we’ve asked employees about the ideal frequency of manager contact, we’ve been surprised at the relationship between greater frequency of contact with managers (daily or multiple times per day) and the perception of high manager effectiveness. In other words, more contact with the manager and higher manager performance ratings are correlated. Moreover – and here’s another paradox – people who say they have frequent contact with their high-performing managers also say they feel more able to work autonomously, with minimal manager oversight.

The best managers, in other words, act like micro-time managers – they spend more small units of time with employees. So, why don’t employees perceive this extra attention as oppressive micromanagement? Because, our research says, the contact is pulled by the employee, not pushed by the manager. Smart managers provide the desired support when defined by the employee’s need for assistance and resources, not by the manager’s need for control. Positive micromanagement focuses on what people require from managers – just-in-time advice about a new work approach, information about an upcoming change, coaching to deal with a difficult peer – rather than on what managers must need to feel in charge.

In many cases, managers succumb to the temptation to micromanage (old definition) because they are technical experts, promoted for their productive prowess, rather than for their leadership abilities. When Google took a hard look at its manager ranks, it found too many people who fit this profile. So, the organization set about to define what makes a great manager. Google defined eight behaviors that characterized the best-performing managers. They uncovered elements like coaching, empowering the team, helping people with career development, and having a clear vision and strategy for the unit. Having strong technical skills and working side-by-side with the team didn’t show up on the list until number eight. Thus the message, as defined by some of the smartest people in the workplace: We need plenty of support from managers, but we don’t need micromanagers who think they are as technically savvy as we are and hover over us to prove it.

Making jobs better by making them harder — but with a twist

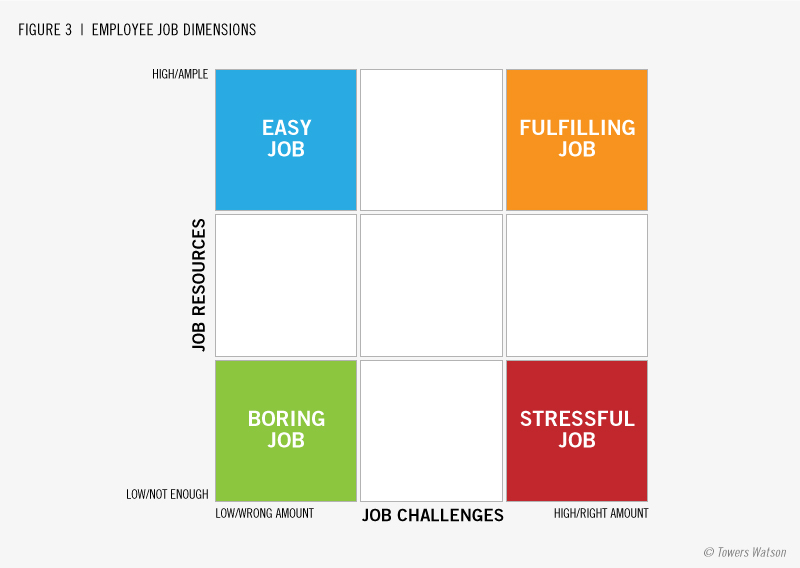

Like the manager role, employees’ jobs can be considered along two fundamental dimensions. One dimension is job challenge, the magnitude of sustained mental or physical effort required to execute the basic job components. Job challenges are high when the jobholder faces frequent demands: urgency to perform, long task lists, complex role requirements and tight time requirements. Balancing job challenges are job resources: support from teammates, problem-solving assistance from a manager, recognition for success, and autonomy in how work is performed. Access to job resources helps people handle large workloads and juggle disparate assignments. The richest and most fulfilling work presents employees with challenges that, when overcome, produce feelings of achievement. Job resources are the key to achieving these feelings.

Figure 3 illustrates the challenge and resource dimensions. The four corners contain labels that reflect the degree of balance. Easy jobs have ample resources but too little challenge. Boring jobs lack both. Stressful jobs – where so many employees find themselves working – are out of balance, with challenges exceeding resources. The best jobs for most employees lie in the upper-right corner, where ample job resources make it possible to overcome challenges, and achieve success and the feelings of accomplishment that result. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi captures this notion when he says that maximum focused engagement in achieving goals “tends to occur when a person’s skills are fully engaged in overcoming a challenge that is just about manageable.”6 Helping employees navigate that small “just about” space is the job of the manager.

What HR Can Do

Human Resources’ first job is to understand and advocate for the importance of the manager position. Beyond that, HR professionals must adopt an evangelistic fervor to identify and build the organization’s manager capability. This means focusing on a few critical requirements.

Review and redefine the manager role

In many organizations, the manager position has become a conglomeration of miscellaneous parts, frustrating both managers and their subordinates. Managers are often expected to perform as individual contributors, while also leading and handling a heavy burden of administrative tasks. Nowhere is this more common than in information technology units.

Human Resources can help by calling a “time out” and analyzing the time requirements of managers on the job. Begin with this question: What is the best way for our managers to help the organization be economically and competitively successful? With the answer to that question in hand, define a manager’s day so that the bulk of time goes to the most competitively important tasks. In many cases, it will be clear that shifting manager time and attention away from personally making widgets to leading and engaging other widget-makers will be the most important change. Data from the Towers Watson 2010 Global Workforce Study indicate that only half of all IT employees believe that their managers have enough time to handle the people aspects of the job. Fixing that problem should be HR’s first job.

Don’t automatically promote the best technicians

Many organizations we work with, especially those with large engineering, programming or scientific populations, believe that only the best technical experts have the know-how and credibility to lead other technical contributors. Google executives believed that, too, until employees told them differently. The advice for HR: Look to promote competent technical performers (say, a 7 on a 1-to-10 scale of discipline-specific excellence) who have demonstrated excellent leadership potential (a 9 on a 1-to-10 leadership potential scale). How do you identify the folks with true capacity for success as managers? Look for managers who:

- Are chosen frequently as team leaders because they have the respect of their peers, not just for their technical knowledge, but also for their empathy and judgment;

- Are known to peers and subordinates as wise counselors on many topics, not just technical ones;

- Show evidence of understanding how the company works, how their units contribute to company success and how their jobs, and those of other functions, fit into the bigger picture;

- Demonstrate the ability to deal successfully with a broad range of personalities, perspectives and interpersonal challenges; and,

- Aspire to hold a leadership position, not only because their compensation will go up, but also because they believe that they have something to contribute to the organization beyond their technical prowess.

Don’t create player/coach positions

Across a range of industries and functions – but nowhere more frequently than in information technology – organizations expect line managers to both perform and oversee work. The goal is leverage: Why can’t we pay one person to do two jobs, the reasoning goes? The problem, of course, is that one person can rarely sustain high performance in two jobs as different as playing and coaching. If the manager’s greatest contribution to competitive advantage comes from energizing and directing the performance of others, shouldn’t the coaching elements of the job take clear precedence over the playing aspects? In the real world, virtually all managers must balance some amount of playing and coaching. The issue is not one of absolutes, but rather of optimal proportion to yield the highest performance of the unit as a whole.

Dealing with the apparent contradictions that come with most manager positions makes the job a tough one, and in many ways, the most difficult job in the organization. Human Resources can do a lot to make the job more manageable and more successful. With properly focused effort, HR can become the most important ally of managers in the middle of the organization. In that way, HR makes what is, perhaps, its most important contribution to organizational success.

Endnotes