Management and leadership have been integral parts of business since humans invented work. For most of the last two decades, though, the manager position has been under direct assault. It’s become a ragged conglomeration of pieces and parts, designed to do too many things and engineered to do none of them well.

In this article, we look at the picture differently. We view supervisors and managers as centers of insight and influence, under appreciated in many organizations but endowed, nevertheless, with the potential to make dramatic contributions to enterprise success. With this foundation, we draw on global research and case examples to develop a five-part performance model that we believe creates a blueprint for the new manager role. Our way of thinking about managers reflects both current workplace reality and enduring human traits. Our goal is to elevate the manager role from message amplifier, process executor and (heaven forbid) progress barrier to powerful source of competitive advantage.

Introduction

It’s time for a new way of looking at the jobs of supervisors and middle managers. Not only because of the aftereffects of the great recession of 2008 and 2009 (and its lingering effects into 2011 and 2012), though that’s part of the reason. The recession has pushed the relationship between employee and employer to a new evolutionary stage, forcing a redefinition of the manager’s role. And not just because the workforce itself has continued to evolve, with a growing sense of independence that requires new leadership skills from managers. And not only because less than 60 percent of employees think their managers perform effectively, a score that suggests deep-seated skepticism about the abilities and contribution of supervisors and managers.

Individually, each of these factors raises concerns about how 21st century managers do and should contribute to their organizations. But, together, they suggest a need to fundamentally redefine what companies should expect from their supervisor and manager ranks and to rethink how to make managers significantly more effective.

Do Managers Really Matter?

Most supervisors and managers, reflecting on their work experience, have wondered about this question at some point in their careers. Many have concluded that the answer may be “No.” In fact, it appears that plenty of employees would like to hide under their desks when faced with the prospect of a promotion into management. A study by Randstad, the global temporary staffing company, found that more than half of employees say they don’t want to move into management roles (Randstad, 2009).

Mindful of the frustration managers often experience, we reframed the question: Do first-level and mid-level managers truly make an important contribution to organizational success, one that organizations should recognize and value more highly? To find the answer, we first looked at the results for a sample of the employee attitude research projects we have performed for hundreds of companies in recent years. We found plenty of evidence that managers do matter — in many important ways. The following bullets include some examples:

• We took a close look at the relationship between employee engagement and organization performance across a population of 16 property and casualty insurance companies. We found a strong association between increased employee engagement and significant increases in financial gains. We then analyzed the data to determine whether a relationship exists between manager effectiveness and employee engagement. Our team worked with one company AAA Northern California, Nevada and Utah to identify engagement survey items and compile them into a manager performance index. Using that index, we correlated the engagement and performance indices across nine major units within the company. We found a 0.63 correlation between manager performance and engagement at this company (1.0 would indicate a perfect linear relationship and zero would mean no relationship). These results suggest a connection between the manager performance and employee engagement measures and, ultimately, between manager performance and financial results.

- We looked at the factors that most directly influence employee orientation to customer service. Across a population of North American retail companies, we found that store management is the strongest single driver of associate engagement, which, in turn, influences customer and quality orientation. These elements, in turn, push up sales growth and performance against sales goals. A similar finding emerged in a customer service analysis we performed for a global technology company. Senior leadership sets the service tone, but local managers create the environment in which a service ethic becomes real for customers.

- When we surveyed 314 companies worldwide about their talent management practices, we learned that less than a quarter believe their managers perform effectively. We were encouraged, however, to find that 68 percent of the surveyed companies (and 72 percent of the highperforming organizations) plan to increase emphasis on improving manager performance in the next three years (Towers Watson, 2010, “Creating a sustainable rewards and talent management model”).

A 2010 study by the Economist Intelligence Unit found that the motivational ability of the immediate line manager is the single most important contributor to employee engagement, ahead of such factors as senior management values, vision and charisma. Chris Bones of Manchester Business School reinforces the point: “There is no real evidence to say that leadership makes a difference. The only people that can help employees reach positive answers to those questions that directly influence engagement, such as ‘Do I feel valued?’ or ‘Is my career progressing?’ are their immediate managers” (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2010).

What’s at stake with manager performance is not just happier and more engaged employees. The real prize for organizations with high-performing supervisors and managers is the competitive advantage they can produce. But what do the best managers do to make the greatest possible contribution to enterprise prosperity? To answer that question, we set about to define an updated model of manager performance, one that reflects both the evolving realities of the workplace and the enduring truths of employee behavior.

The Manager Performance Model

We used data from our Global Workforce Study to develop a manager performance model that captures the key elements of our client-specific and industry-focused research (Towers Watson, 2010, “The New Employment Deal: How Far, How Fast and How Enduring”). The analysis produced a model that encompasses five categories of performance requirements. The factors in the performance model aren’t by themselves shocking — it’s how they are executed that makes the difference between great managers and mediocre ones.

Performance Category 1 – Executing Tasks

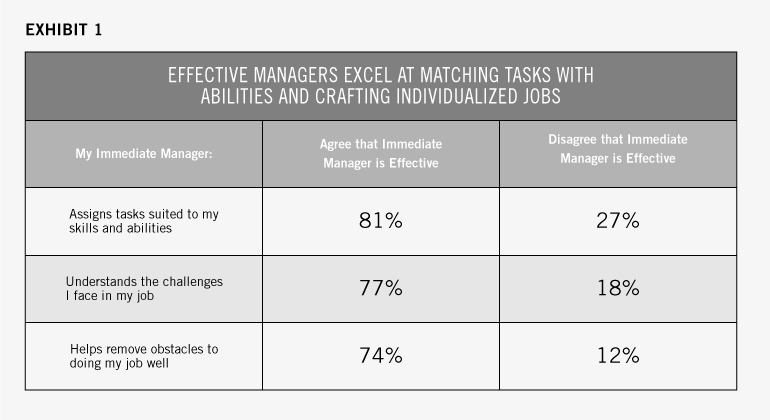

This element consists of planning work, clarifying job-related roles, structuring specific job tasks, monitoring performance and making the necessary adjustments to ensure that work meets organizational needs and supports business strategy. These factors come readily to mind when we think about the manager’s basic responsibility for ensuring that a unit achieves its strategy contribution goals. Overseeing task execution is, in many ways, the most conventional aspect of the manager’s job. The exhibit below shows the wide gap between effective and ineffective managers, as rated by employee respondents to our Global Workforce Study.

This element consists of planning work, clarifying job-related roles, structuring specific job tasks, monitoring performance and making the necessary adjustments to ensure that work meets organizational needs and supports business strategy. These factors come readily to mind when we think about the manager’s basic responsibility for ensuring that a unit achieves its strategy contribution goals. Overseeing task execution is, in many ways, the most conventional aspect of the manager’s job. The exhibit below shows the wide gap between effective and ineffective managers, as rated by employee respondents to our Global Workforce Study.

Solidly performing managers use the available planning tools effectively, assign work fairly across the work group and treat employees equally well. These are necessary but not sufficient requirements for effective performance. In our analysis, outstanding managers stood out by doing significantly better in one key area: helping employees craft jobs that have ample energizing elements (such as interesting work and fulfilling team relationships) and the right level of challenge (neither too much nor too little of factors like a broad role and a sense of urgency) with the fewest possible performance obstacles (role ambiguity and organizational politics, for instance). Outstanding managers achieved the elusive alignment between individually engaging, purposeful work and jobs that contribute to the organization’s ability to achieve and sustain a marketplace lead.

Performance Category 2 – Developing People

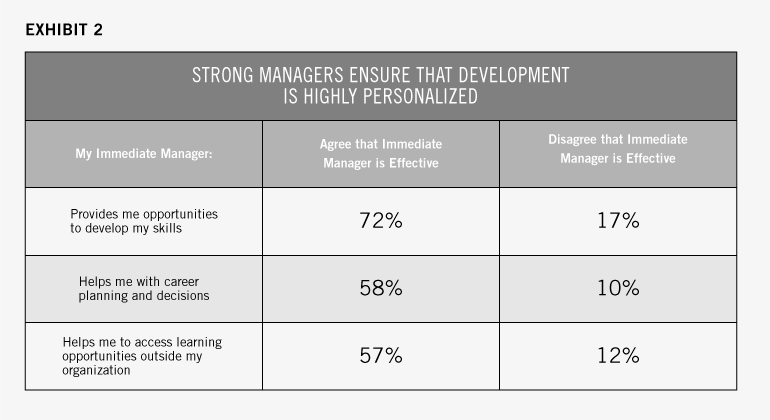

The next element of the performance model calls for managers to create opportunities for each employee to add to her storehouse of skills and knowledge. As Exhibit 2 shows, effective managers understand the “me” message — they personalize each employee’s development experience.

The next element of the performance model calls for managers to create opportunities for each employee to add to her storehouse of skills and knowledge. As Exhibit 2 shows, effective managers understand the “me” message — they personalize each employee’s development experience.

The highest performing managers don’t just connect people with training, coach them or give frequent feedback, however. These are table stakes. To be truly effective, they must also create networks of internal and external learning contacts for employees. In a study of attorneys at prestigious New York law firms, researchers Monica Higgins and David Thomas from the Harvard Business School found that having an array of developmental contacts within the organization did more for young lawyers striving for partnership than did having a single, even senior and effective, mentoring contact. They concluded, “Our results show that while the quality of an individual’s primary developmental relationship does affect short-term career outcomes such as work satisfaction and intentions to remain

Performance Category 3 – Delivering the Deal

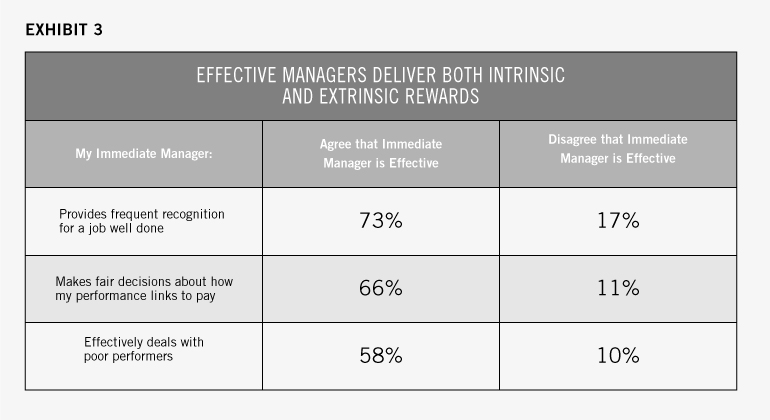

Managers play a central role in brokering the exchange of each employee’s investment of human capital (knowledge, skills, talent and behavior) for the array of financial and nonfinancial, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards they receive. Managers’ development efforts helped employees build their human capital. More than this, the manager also must ensure that each individual receives an adequate return on the investment of that asset. We refer to this reciprocal arrangement as the deal between employee and enterprise.

Managers play a central role in brokering the exchange of each employee’s investment of human capital (knowledge, skills, talent and behavior) for the array of financial and nonfinancial, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards they receive. Managers’ development efforts helped employees build their human capital. More than this, the manager also must ensure that each individual receives an adequate return on the investment of that asset. We refer to this reciprocal arrangement as the deal between employee and enterprise.

It’s hardly news that people work for reasons that go much deeper than financial rewards. Decades of research have shown that individuals are energized by intrinsic motivations that financial rewards can’t address. Managers have responsibility for bringing these kinds of intrinsically fulfilling elements into alignment with what the organization needs to achieve strategic success. Solidly performing managers apply the organization’s reward systems equitably. They adhere to the company’s stated (though rarely well executed) pay-for-performance philosophy and do their best to administer reward systems effectively. But managers who strive for excellent performance go well beyond these basics. They understand that pay frequently fails to reinforce performance and that ownership behavior doesn’t come from holding a miniscule portion of a company’s equity. Rather, they use the entire portfolio of intrinsic rewards at their disposal (satisfying tasks, opportunities to master skills, recognition for success) to make employees feel individually appreciated. When we survey managers, we find that the most astute among them are aware of the power of customizing these reward areas. Exhibit 3 illustrates how employees evaluate effective and ineffective managers on this critical performance criterion.

Think about a manager whose unit has two people with similar backgrounds and experience but very different ambitions. One is an aspiring star contributor; the other has designs on a top executive position. Each should have a customized deal that recognizes his or her particular needs and career goals. The Star Contributor, for example, might require a rapid succession of high profile projects and exposure to industry-leading thinkers as a reward for performance. The Future Executive, in contrast, might be willing to accept a longer-term quid pro quo for his contribution, progressing steadily through a sequence of incrementally broader leadership roles with increasing visibility to senior executives.

In describing what they call sustainable management organizations (SMOs), agile, adaptable companies that achieve extended success by addressing the demands of multiple stakeholder groups, authors Ed Lawler and Chris Worley support the notion of individually customized deals: “Given the large individual differences that exist in people’s reward, career, and work preferences, in SMOs an individualized and differentiated reward approach is needed … Organizations can give individuals choices in terms of what type of incentive rewards they might receive, for example, cash or stock, and indeed what kind of incentive plan they are on (a lot of or little pay at risk) … More broadly applicable is giving individuals choices with respect to the fringe benefits that they receive and … in their work arrangements and working conditions” (Lawler and Crowley, 2010).

Performance Category 4 – Energizing Change

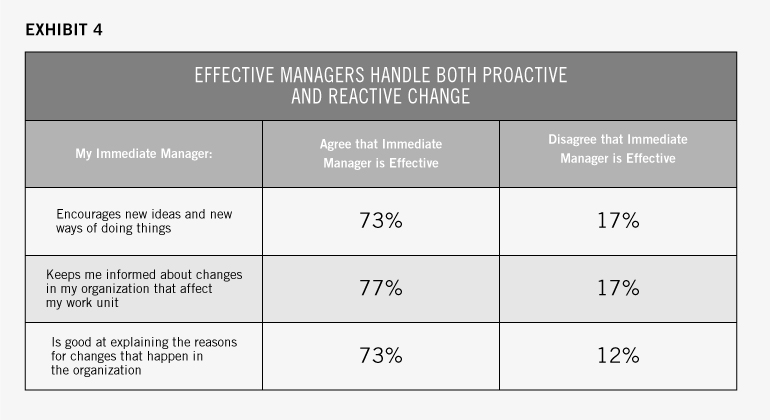

Effective managers envision, plan for and create the future. Sometimes, this requires them to respond to change that is imposed and unavoidable — reorganization, strategic redirection or downsizing, for example. In other cases, innovation and creativity may spark the change, as people develop new offerings or find better ways to work. As Exhibit 4 indicates, there are wide differences between the performance of effective and ineffective managers in both change arenas.

Effective managers envision, plan for and create the future. Sometimes, this requires them to respond to change that is imposed and unavoidable — reorganization, strategic redirection or downsizing, for example. In other cases, innovation and creativity may spark the change, as people develop new offerings or find better ways to work. As Exhibit 4 indicates, there are wide differences between the performance of effective and ineffective managers in both change arenas.

Innovation-driven change is affirmative and forward-looking (though not necessarily gentle or easy). The best managers handle this by encouraging employees to focus intently on improving products, services and work processes. But change can have a dark side as well, when economic conditions, competitor success or unexpected shifts in customer behavior make adapting a requirement merely for survival. Our research has identified two factors required to sustain employee engagement through challenging periods like these.

We call one factor performance support. Managers provide unit-specific support for performance by making sure employees have the wherewithal to execute their jobs effectively. Managers get high performance support scores when employees perceive that:

- physical work conditions are comfortable and conducive to high productivity;

- all the resources and tools required to do their jobs (physical, financial, informational) are readily available;

- safety on the job is never compromised, even at the expense of production; and

- unit staffing is sufficient to ensure that the workload is manageable and fairly allocated.

The second sustainable engagement factor is an organizational climate that promotes employees’ physical, psychological and social health. We call this well-being. Employee well-being is important for reasons that extend beyond sustaining engagement and providing regenerative power in the face of organizational change. The well-being of the workforce also has major implications for organizations’ health care costs. By one estimate, American employers spend $13,000 annually per employee in total direct and indirect health related costs. Plus, for every dollar spent on medical services and pharmaceuticals, companies lose another $2.30 on health-related productivity costs — the expenses associated with absenteeism and low productivity. Depression is the single most expensive health condition, carrying an annual total cost of more than $350 per full-time employee (Loeppke, 2009). The requirements for managers to foster employee well-being and lower these costs are embedded in the performance model: ensuring that work tasks align with employee ability; helping people master their jobs; managing workloads to allow for a balance between work and personal life; reducing workplace stress. By reducing the care requirements associated with depression and anxiety alone, managers can make a major financial contribution to their companies.

Add to these factors the competitive advantages that accrue to companies whose employees continue to innovate and produce efficiently even in challenging economic and competitive environments. This advantage produces impressive financial returns. In a Towers Watson study of 50 global companies, we found that companies with low employee engagement produced operating margins of 9.9 percent on average. Organizations that raised engagement significantly turned in operating margins of 14.3 percent. But companies with high engagement, sustained with both performance support and employee well-being, had average margins of 27.4 percent, almost three times the performance of low-engagement organizations.

We believe this four-part model — executing tasks, developing people, delivering the deal and energizing change — appropriately balances individual interests with those of the enterprise. Although the four manager performance components represent discrete categories, real success comes when managers integrate them into a seamless set of behaviors. For example, in performing their task-related responsibilities, strong managers help people craft jobs that contribute to skillbuilding and mastery. Likewise, they can ensure that employees’ developmental efforts build skills that contribute to the creation and implementation of new and improved work systems and technologies. These, in turn, can fuel positive change. The best-performing managers can frame learning opportunities as rewards in themselves, especially for highperforming employees who value learning and want to get ahead.

Our manager performance architecture needs just one more component: a foundation.

The Foundation — Authenticity and Trust

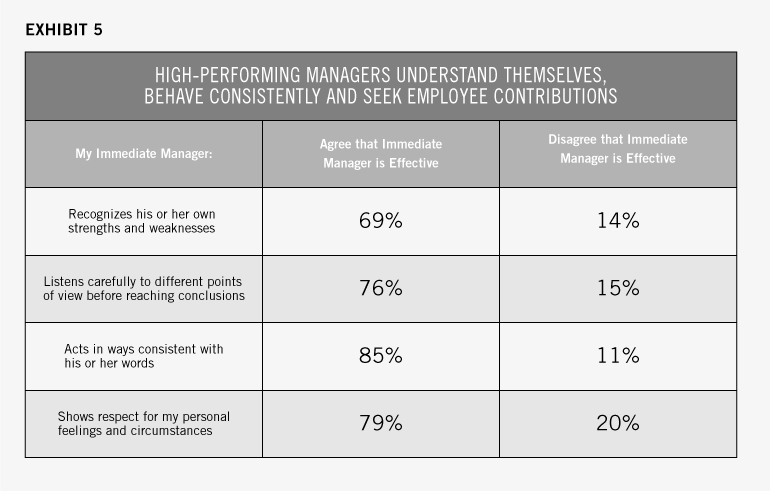

To this point, we’ve described manager performance requirements that employees, and the rest of the organization, would observe and experience. But effective managers don’t define their roles solely through the eyes of others. Instead, strong managers hold themselves to an internal, self-defined standard of acting and speaking, regardless of the requirements imposed by the external world. Scholars of leadership call this authenticity (Walumbwa, 2008). As with the other elements of the performance model, our research uncovered a set of dimensions that differentiate effective and ineffective performers. Examples of these appear in Exhibit 5.

The data in Exhibit 5 show the dramatic differences between managers rated by employees as effective and those whose performance falls short. Every manager, of course, must act with integrity. But the best managers also display the humility, intellectual honesty, interpersonal sensitivity and behavioral consistency required to perform effectively across all core elements of the manager model. These elements form a basis for establishment of a trusting relationship between manager and employee.

Key Themes for Managers

Cutting across the five elements of the model are three fundamental themes that should govern how managers should approach the performance challenge:

- Treat employees as individual investors, not as organizational assets.

- Manage the paradox of availability.

- Perform the manager role from offstage.

Here’s what each of those recommendations means for managers.

Treat Employees as Individual Investors, Not as Organizational Assets

Throughout the last 15 years or so, “workers as assets” has become the dominant metaphor applied to the people who work in modern organizations. The asset metaphor shortchanges workers by placing them in the same class as drill presses, buses and computers. The asset is not the person, but rather the human capital that each person possesses — the skills, knowledge, talents and behaviors that he or she brings to work every Monday morning. High ROI on human capital investment leads to greater contribution and vice versa. And while well-invested human capital benefits both individual and organization, let there be no ambiguity about who owns it: people, not companies, own human capital. People, not companies, decide how much will be contributed and how much withheld (Davenport, 1999).

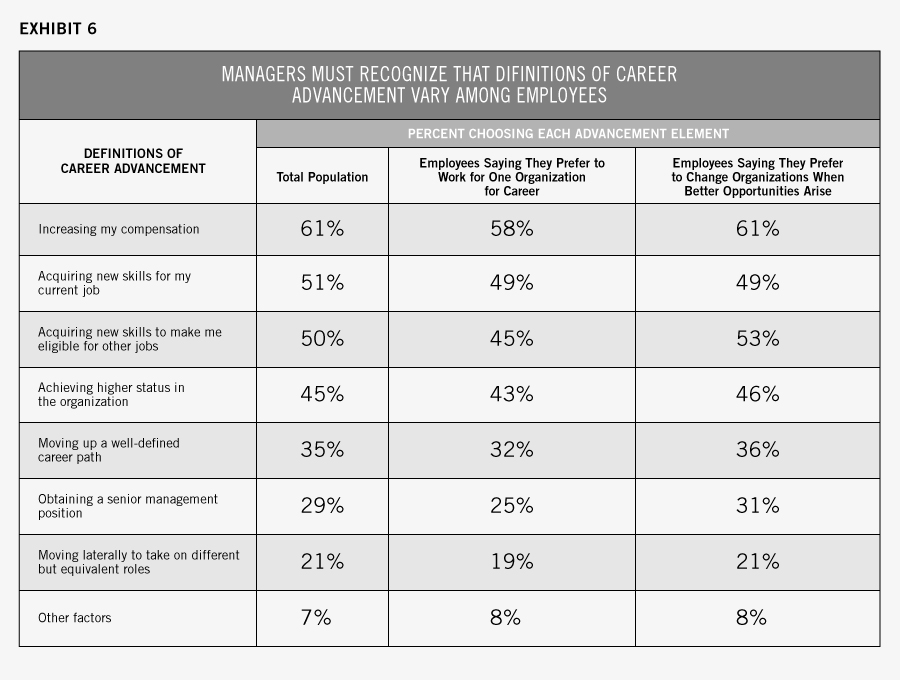

Employees want managers who pay attention to each person’s talents and interests and customize their work, their development opportunities and their rewards to yield the desired return on human capital investment. As Exhibit 6 suggests, such factors as individual commitment to the organization may influence which elements of the reward portfolio, job content and development plan an individual values most.

Most work groups will have some employees who take the long view. They would prefer to work for a single organization for as long as possible, presuming they get paid reasonably well and receive opportunities to learn skills that help them do their jobs better. Other members of the team, perhaps made skeptical by watching their friends lose their jobs during the last downsizing, will look at the implicit employment contract differently. Unconstrained by loyalty to the company, they will tend to move early and often for better opportunities. They too want to increase their compensation over time, but they care even more than the long-term folks about growing their skills for the next job (in their organization or another one) and moving up the ladder into senior management (in their present company or somewhere else). If your enterprise can provide these opportunities, they may well stay put. But absent a way to move vertically and increase their organizational status, they will move on to where the grass looks greener.

These patterns may vary within any specific unit, of course, but a key point remains: Effective managers must understand what each individual requires as his or her return on human capital investment and work the organizational systems to deliver that value. This customization requirement cuts across all elements of the performance model: job structure supporting task execution, human capital development, delivery of the deal and environment supporting resilience in the face of change.

Manage the Paradox of Availability

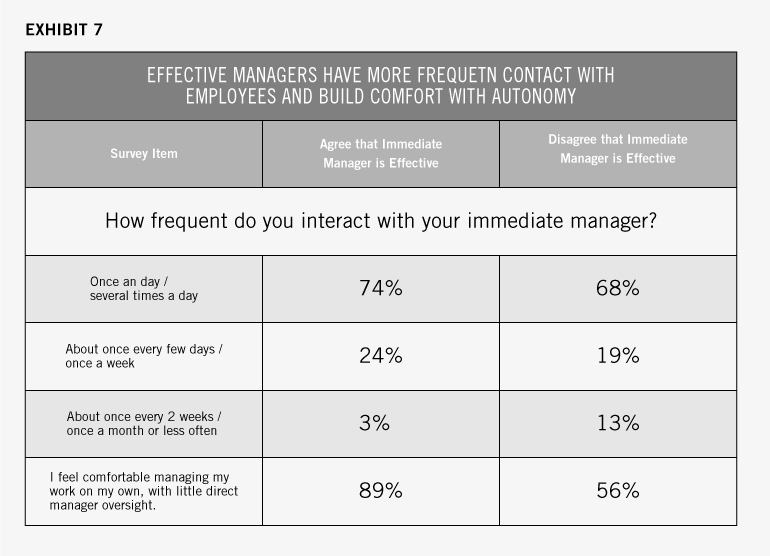

Our manager performance model is predicated on a strong version of the fundamental raison d’être for managers — that the manager position exists to increase the productivity of employees. Respondents to our global survey said, however, that less than 50 percent of managers have enough time to spend on the people aspects of their job. We discovered that effective managers differ significantly from the less-effective counterparts in how frequently they have contact with employees. Exhibit 7 presents the data.

Our manager performance model is predicated on a strong version of the fundamental raison d’être for managers — that the manager position exists to increase the productivity of employees. Respondents to our global survey said, however, that less than 50 percent of managers have enough time to spend on the people aspects of their job. We discovered that effective managers differ significantly from the less-effective counterparts in how frequently they have contact with employees. Exhibit 7 presents the data.

Skillful managers perform a clever sleight of hand — they have more frequent contact with employees and yet they enable employees to have greater comfort doing their work with less manager oversight. How do they create this paradox? By employing what we call punctuated availability. They don’t sit behind their computer screens and make employees wait to get advice about how to approach a task, coaching to build a key skill, explanation of some aspect of their deal or reassurance about an organizational change. Instead, they make themselves accessible to employees when employees need them. They are just-in-time managers: They remain available but don’t hover; they stay accessible but don’t micromanage.

A Philippines-based call center organization, eTelecare, provides an instructive case. In an industry where managers often have 20 or more employees reporting to them, eTelecare has a ratio of customer service representatives to team leaders of just eight to one, less than half the industry norm. Supervisors at eTelecare invest an hour a week coaching each employee, on top of the time they spend monitoring employee performance. They also put at least 10 percent of their time each week into developing process improvements that help employees do their work independently. Employees report that team leaders, freed up from the burdens of wide spans, have more time to help employees develop their service skills and technical knowledge. This investment in staff development enables eTelecare to build the skills of its representatives quickly. Some staff members make the leap from entry level to licensed securities sales representative in just 18 months (Hagel, 2004).

As founder Derek Holley said: “Our clients don’t just come to us because of our cost advantage relative to their in-house U.S. operations; they want to be sure that we will deliver superior service to their customers. They stay with us because they simply can’t replicate our service levels in their own operations” (Hagel, 2009). By giving managers the time to focus on growing employees’ human capital, eTelecare has been able to reshuffle the competitive deck in its business, delivering a differentiated offering in an industry that usually cares mostly about cost.

Perform the Manager Role from Offstage

The paradox of availability has a corollary: The best managers concentrate on managing the work environment rather than the employees. Our research suggests that effective 21st century managers behave like sculptors (working with employees to craft job roles that fit both individual needs and organizational requirements); catalysts (initiating action in the workplace but often avoiding direct involvement); and conductors (orchestrating the efforts of others and enriching the environment in which they perform, while not actually playing the music). These roles mean giving people both the freedom to act independently and the ability to do so successfully — in other words, providing for effective autonomy. Fostering effective autonomy has emerged from our research as an increasingly important engagement factor within the post-millennium workforce.

Autonomy differs in important ways from empowerment. When people speak of empowerment, they generally refer to the transfer of power from a manager to an employee. It’s a zero-sum game, where the manager’s power diminishes by the amount given to the employee. The empowerment exchange between manager and employee sounds like this: Manager: “I have power and I am transferring some of it to you.” Employee: “Thanks, boss.”

Autonomy refers to something subtly but significantly different. Essentially, it means self-rule, incorporating the notion of freedom to decide how best to get things done. Rather than subdividing a given quantity of power, autonomy adds to the total amount of power available to do work. The autonomy dialogue sounds different: Manager: “You are competent and engaged in your work. You know the results that are expected. How do you want to do your job?” Employee: “I’ll get back to you.”

For an example of workplace freedom, consider the case of Zappos, the quirky online retailer, now part of Amazon.com. Zappos has moved as far from the call-center-as-electronic sweatshop as it’s possible to go. “We do our best to hire positive people and put them in an environment where the positive thinking is reinforced,” said Tony Hsieh, Zappos chief executive (O’Brien, 2009). That environment is script-free and freedom-rich. Jobs are designed to let people use their creativity and their imaginations to delight customers. In one case overheard by a magazine reporter, a customer complained that her boots from Zappos had begun leaking after almost a year of use. The rep not only sent out a new pair, in spite of a policy that used shoes can’t be returned, but also mailed the customer a handwritten thank you note (O’Brien, 2009). This kind of initiative can occur only within a flexible job structure that affords substantial freedom to act autonomously.

What Human Resources Can Do

HR’s first job is advocacy, urging executives to accept that the performance model laid out here produces better economic results for the organization than other manager job concepts. They must become evangelists for the role performance elements that make it possible for managers to fulfill the potential we’ve identified. Here are some of the specific requirements HR must meet to maximize its contribution to manager excellence:

- Don’t compromise on the required attributes when filling open supervisor and manager positions. Examine your compensation systems, titling conventions and cultural norms of prestige. Don’t allow these factors to drive your company to promote people into positions where they can do more harm than good to the organization, their employees and themselves. Waiting for the right candidate — people who have demonstrated the potential to execute the five performance elements of our model — is better than putting the wrong person in any supervisor or manager job. The wait is worth it. Whatever benefit comes from filling a position quickly soon disappears if employee engagement, development, performance and well-being are sacrificed.

- Make it a top priority to do something about the low-performing managers in the organization. Some should go back to being individual contributors — and they would probably be happier if they could. Others simply may not belong in the company. Don’t prolong their agony and yours by keeping them in positions that drain their energy and hinder organizational success.

- Consider letting individual contributors have a trial run in their first supervisor position, perhaps overseeing a specific initiative or a modest project. Make it a brief, no-harm-no-foul experience, and then decide whether they can best contribute as managers or as direct output producers (but not both). Let them choose the right path with impunity.

- Define manager performance metrics that reflect the full contribution of the role. Don’t overemphasize the manager’s direct production. Instead, focus chiefly on the unit’s production and financial performance, but also monitor the growth of employees’ human capital, the state of their engagement and their levels of perceived well-being. Use the elements set out in Exhibits 1 through 5 as an index for assessing manager performance. Of course, performance will vary across the criteria, ranging from pretty strong in some areas for some managers to fairly poor in other areas for other managers. The encouraging point is that they all have a lot to gain from improving. By enhancing their competence in each area, managers not only improve their own performance, but also the ability of their teams to contribute to the competitive success of the enterprise.

- Make a specific effort to prepare managers to play their part in delivering the deal. Don’t make them solve mysteries about the components or intention of the organization’s reward systems. Give them latitude to apply those systems with judgment and individual sensitivity.

- Make sure your managers have full information about the organization’s learning and development opportunities. In particular, help them map the available cross organization moves, so that they can guide employees in their use and integrate them suitably with other learning strategies. Also ensure that managers’ efforts to help employees develop their human capital align with goal setting, performance evaluation and rewards. HR must deliver a fully articulated system that managers can apply.

- Structure managers’ reward portfolios — the deal they have with the organization — so they align with these ways of measuring. Don’t tilt the pay system toward individual output.

- Don’t give in to the temptation to shift HR duties to managers without a careful assessment of the workload and time allocation implications. Our performance model places high enough demands on them. Don’t make managers’ jobs harder by giving them a heavy load of HR administration tasks.

- Remember that employee well-being is a whole-system concept that requires close connection between managers and HR. Make it a campaign to work with managers to understand and improve well-being. The potential health care cost savings are dramatic.

- Never put managers in a position where they must compromise the trust they have built with employees. This means always ensuring that they have full information about the organization and its strategy, challenges and position in the marketplace. It also means giving them freedom to respond to organizational change in ways that preserve their integrity and reinforce their authenticity.

HR’s relationship with managers should have many facets — ally, trusted adviser, coach — with each party playing these roles for the other as the situation requires. When the relationship works best, manager and HR will act as partners — investment partners, business partners, sparring partners. After all, HR and line managers have a common goal: make the enterprise competitively successful through the contributed strengths of the employees who work there. They should need no more powerful bond than that goal and no greater reason to do everything possible to ensure that the manager population becomes a source of sustainable success.

References

Davenport, T.O. (1999) Human capital: What it is and why people invest it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 5.

Economist Intelligence Unit (2010). Re-engaging with engagement: Views from the boardroom on employee engagement.

Hagel, J. (2004) Capturing the real value of offshoring in Asia,” Working Paper, 6.

Hagel, J., Brown, J.S., & Davison, L. Talent is everything. (2009) The Conference Board Review, May/June, 6.

Higgins, M. C., & Thomas, D. A. (2001) Constellations and careers: Toward understanding the effects of multiple developmental Relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 240.

Lawler, E.E., & Worley, C.G., with Creelman, D. (2010) Management reset: Organizing for Sustainable Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 218.

Loeppke, R. and others. (2009). Health and productivity as a business strategy: A multiemployer study. Journal of Organizational and Environmental Medicine, 51, no. 4, 411, 423.

O’Brien, J.M. (2009, January 22)). Zappos knows how to kick it. Retrieved from http://money .cnn.com/2009/01/15/news/companies/Zappos_best_companies _obrien.fortune/index.htm.

Randstad, Inc. (2009). Managers of tomorrow: Setting a new standard. 2009 World of Work Topic Report, 2.

Towers Watson. (2010). Creating a sustainable rewards and talent management model.

Towers Watson. (2010). The new employment deal: How far, how fast and how enduring.

Walumbwa, F.O. and others. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34, no. 1, 95–97.