Investing time and effort to uncover and mitigate today’s stressors for employees can help employers avoid tomorrow’s more damaging and expensive consequences. A comprehensive assessment of workplace stress can generate a substantial return on this investment, measured in enhanced individual well-being, reduced health care and disability costs and improved company performance. This article discusses the structure of stress diagnostics, the dimensions of those diagnostics, leading and lagging indicators of employee stress and how employers can use diagnostics to take actions that benefit employers and employees alike.

By Thomas O. Davenport | Willis Towers Watson and Jeff Levin-Scherz | Willis Towers Watson

Since homo sapiens first walked onto the evolutionary stage, humankind has experienced pressure from the environment. Avoiding threats, such as a sneak attack from the clan in the next valley over, and taking advantage of opportunities, e.g., a tasty prey item, call for an immediate mental and physical response. When the intense moment has passed, our fight-or-flight system should return to a state of quietude that allows for regeneration before the next crisis.

In the 21st century workplace, however, a multitude of social, psychological, emotional and financial threats can chronically activate our stress-response systems. By one estimate, our stress-driven physiological reactions kick in as many as 50 times per day.1 This constant stress can threaten physical, psychological and emotional health. Organization leaders now realize that the effects of workplace stress have profound significance, not only for individual well-being but also for organizational performance. An organization’s response to workplace stress depends on leaders who thoroughly understand workplace stressors and can formulate an effective strategy to respond to the potentially unhealthy aspects of the work environment. A comprehensive diagnostic assessment of workplace stress can help an organization understand the specific causes of stress among its employees as a critical first step in developing strategies to address those causes.

The Structure of Stress Diagnostics

Stress is an individual’s mental, physical or emotional reaction to perceived or actual stressors. Stressors, in turn, encompass a full range of internal and external stimuli experienced by an individual. External stimuli can come from the work environment or from experiences outside the workplace. The litany of workplace stressors is familiar: too much work for the time and staffing available, too little reward for the contribution expected, too much conflict among peers or between employees and managers, too little clarity about performance expectations.

Internal physical and emotional stressors also affect workers, as do perceived financial pressures. Acute stressors activate a complex stress response system that involves an array of organs and chemicals, signals and feedback. When these systems are continuously activated, damaging health consequences can include increased blood pressure, heightened risk of stroke, suppressed immune function, increased risk of depression and greater vulnerability to orthopedic problems.

Given this context, stress measurement tools must focus on both the causes and consequences of workplace stress. Organizations should pay attention to indicators that reveal potential stressors as well as to the downstream physical, psychological and emotional implications of stress.

Diagnostic Dimensions

An organizational stress assessment must answer four questions:

- How intense is stress in various parts of the enterprise?

- What is causing it?

- What are the current and likely future consequences of present stress levels?

- What will be the most effective responses, both for individuals and for the organization overall?

The diagnostics required to answer these questions fall along two dimensions: time horizon (leading and lagging indicators) and type of cost (direct and indirect).

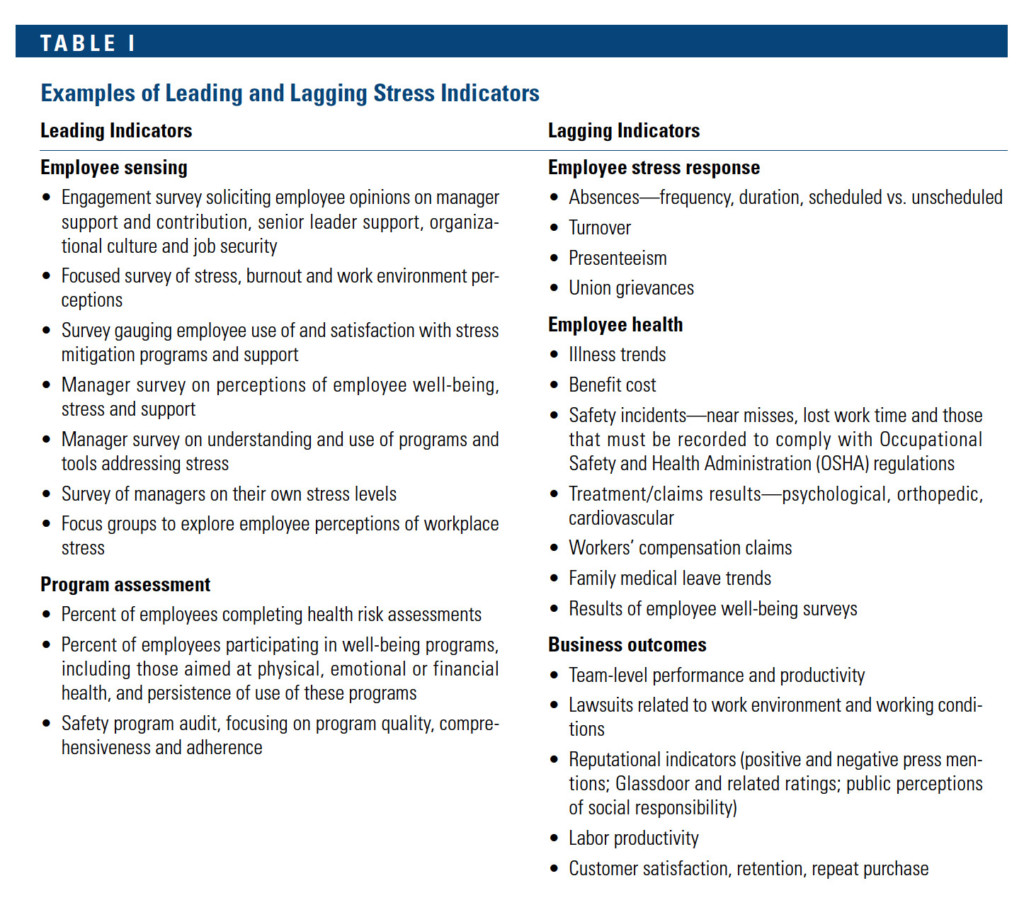

Leading indicators give warning about the prevalence of stressors that repeatedly stimulate individuals’ stress response systems, point to where pressures are felt most intensely and suggest the possible downstream effects. Because leading indicators encompass measures that change before stress has begun to have harmful effects, they can help predict what might happen in the future. Understanding the messages embedded in leading indicators gives organizations the opportunity to anticipate and prevent the subsequent physical, psychological and emotional results of continued exposure to workplace stressors.

Lagging indicators, by contrast, reflect the outcomes of extended periods of stress and confirm that stress-related problems have occurred. Employers should monitor lagging indicators to identify potential actions and to evaluate the effectiveness of current initiatives. Table I shows examples of leading and lagging indicators.

Some costs are explicit or direct (health care claims, for instance, which have identifiable monetary value). Others are implicit or indirect (such as unscheduled employee absence, which has real financial implications but is difficult to denominate in monetary terms in many industries).

The case studies that follow describe how two organizations used leading and lagging indicators to assess potential causes and outcomes of stress.

Leading Indicator—Analyzing the Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Disability at a Major Bank

A major North American bank wanted to diagnose links among employee engagement scores, workplace stressors and worker disability. The bank routinely receives high rankings as a place to work, so organization management was especially concerned about a subtle but alarming trend of declining employee engagement scores.

Bank leaders knew that declining engagement can be a leading indicator of emerging workplace stress issues, which can, in turn, prompt people to take disability leave (a potentially significant explicit cost). An analysis of the relationship between employee attitude and level of disability leave showed that those who took disability leave judged their work environments to be:

- Less open. Differences of opinion within work groups often were not discussed, and people perceived it was less safe to speak up.

- Less flexible. Managers were less likely to allow people latitude to meet personal and family needs.

- Less fair. Employees expressed lower confidence that their performance was assessed fairly and more concern that broader management decisions about employees were not fair.

- Less performance-supporting. Employees on disability leave revealed heightened concern about whether the goals against which they were evaluated were achievable.

The findings underscored the effects an employee’s immediate manager can have on the employee’s perception of the work environment and the stressors he or she experiences. Armed with a better understanding of the effects of manager behaviors on employee mental health, the bank took action to try to preempt costly future disability problems.

The learning and development team created an e-learning program to improve manager performance in identifying and responding to stress-related behavioral symptoms. The training also instructs managers about when to take direct action to help an employee deal with a stressful situation and when to refer the employee to a medical expert or other professional practitioner. The bank’s goal is to equip managers to recognize the early signs of employee stress and to react before stress leads to health problems that can require disability treatment.

Lagging Indicator: Analyzing the Reasons for High Absence at a Mass Media Company

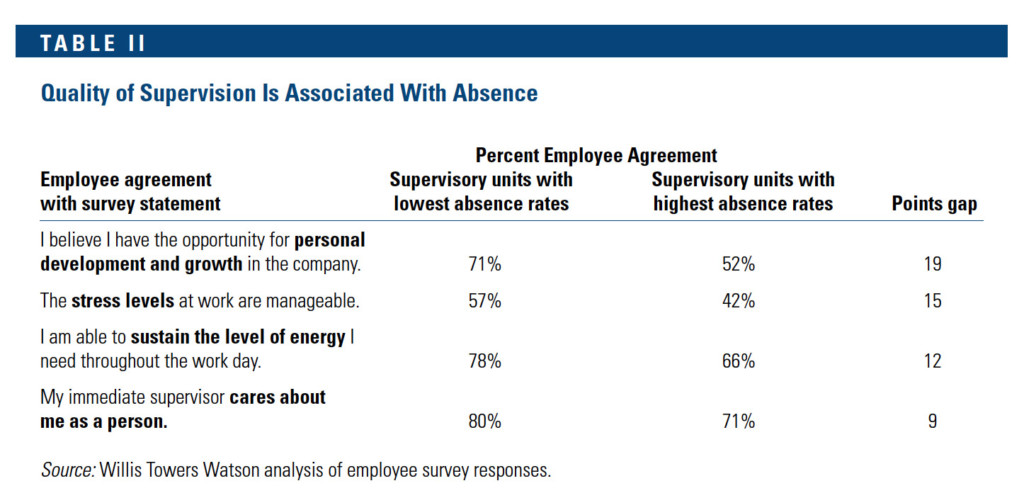

A large mass media company wanted to find the causes of high absenteeism in its call centers. Unscheduled absence is a common problem in call centers, especially among employees who must deal with incoming calls from unhappy customers. Absence trends across 51 call centers were analyzed, linking data from the company’s human resource information system with findings from a survey of employee perceptions of the work environment. The project team also conducted focus groups with employees.

As shown in Table II, the work environment survey revealed a strong correlation between lower absence rates and positive employee perceptions of development opportunity, stress, energy and supervisor concern.

The data suggest that higher performing supervisors may reduce workplace stress and help people cope with the stressors that come with working in a contact center. Diagnostic analysis showed that, in low-absence groups with better performing supervisors, employees gave higher scores to a list of factors:

- Work schedules that enabled balancing work and family life

- Enough staff for the amount of work to be done

- Employees’ involvement in decisions that affect their work

- Perception of flexibility to provide good service to customers

- Personal growth opportunities

- Fair performance evaluations

In response, the analysis team recommended reviewing scheduling policies to allow for greater flexibility. The team also recommended changes to the hiring processes to make it easier to identify candidates most likely to show resilience to the pressures associated with call center jobs. Finally, the team produced a set of recommendations to improve supervisor performance and work unit staffing structure, recognizing the role supervisors play in influencing both the presence of stressors and individuals’ responses to them.

In each of these case studies, segmentation of the data— by employee location, business unit, job type and tenure, for example—was critical to the analysis. Stress, after all, is an individual phenomenon that often results from highly personal and localized causes. Responses, whether organizationwide programs or unit-specific actions, must feel and be relevant to individual employees working in specific environments.

Using Diagnostics

The effort to collect and analyze diagnostic information has value only if the analysis leads to effective action in one or more of three categories:

- Modify the stressors that employees experience. Reduce or eliminate stressors or transform sources of stress and pressure into opportunities for challenge and fulfillment.

- Change individuals’ responses to stressors. Provide opportunities for people to enhance their personal capability to withstand—and be productive in spite of—the stressors they can’t avoid in their working lives.

- Increase access to professional help. Improve the availability of physical, psychological and emotional health treatment to help ameliorate the consequences of high workplace stress.

An organization might react initially to worrisome leading indicators by identifying and reducing the sources of stress: increasing staffing in a specific location (to better spread workloads), relaxing deadlines in a highly pressured production unit (to decrease risky behaviors driven by time pressure) or removing obvious safety hazards in an outdated factory, for instance.

Employers also can take steps to increase employees’ resilience when faced with stress, perhaps through meditation, mindfulness training or yoga. Emerging evidence suggests that mind-body programs like these may yield benefits through decreased stress that leads to declines in medical utilization and medical insurance claims, as well as increased productivity.2

No Action Is Not an Option

Workplace stress is a fact of modern working life, with potentially enormous impact on the physical, emotional and even financial health of employees, along with adverse economic and cultural implications for organizations. Ignoring stress and its implications is, therefore, not an option.

Conscientious leaders can recognize and address workplace stress by using the output from a comprehensive stress diagnostic evaluation. But diagnosis carries a responsibility, because duty to act follows knowledge.

Endnotes

- A. Crum, P. Salovey and S. Achor, “Rethinking Stress: The Role of Mindsets in Determining the Stress Response,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2013, Vol. 104, No. 4, p. 726.

- R. Wolever and others, “Effective and Viable Mind-body Stress Reduction in the Workplace: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 17(2), April 2012, p. 256.

International Society of Certified Employee Benefit Specialists

Reprinted from the First Quarter 2017 issue of BENEFITS QUARTERLY, published by the International Society of Certified Employee Benefit Specialists. With the exception of official Society announcements, the opinions given in articles are those of the authors. The International Society of Certified Employee Benefit Specialists disclaims responsibility for views expressed and statements made in articles published. No further transmission or electronic distribution of this material is permitted without permission. Subscription information can be found at iscebs.org.

©2017 International Society of Certified Employee Benefit Specialists

AUTHORS

Thomas O. Davenport is a consulting director with Willis Towers Watson, a global human resources consulting firm. He provides consulting services on manager effectiveness, employee and organization research, and reward strategy to clients across a broad range of industries. Davenport is the author of three books:

- Manager Redefined: The Competitive Advantage in the Middle of Your Organization

- Human Capital: What It Is and Why People Invest It

- The Stress-Reduction Pyramid: A Guide to Managing the Greatest Threat to Employee Health and Productivity

Jeff Levin-Scherz is the co-leader of the North American health management practice at Willis Towers Watson. He is the clinical and strategy lead on projects to improve employee health and increase cost-effectiveness through innovative programs, rigorous analytics and effective incentive programs. Levin-Scherz previously has served in physician executive positions in provider organizations and within health care finance. He is also an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and the School of Public Health, where he teaches courses on managing heath care costs and provider payment.