For many of us who toil in the modern workplace, it sometimes seems the main exercise we get comes from aerobic stress. Much like a session on the stair master, stress fires up our cardiovascular systems with adrenaline, gets our hormones pumping, and pushes blood to the big muscles that enable us to do heavy lifting. But unlike that hour in the gym, stress is killing us. It drives up health care costs, makes absenteeism worse, and turns people into desk-bound zombies.

A well-conceived manager-training program can significantly improve managers’ ability to recognize and deal with the stress causing factors that plague many work units. But that training must engender the right insights and build distinctly relevant skills. This article describes the areas revealed by Towers Watson research and client experience to be instrumental to addressing the sources of stress that arise as people go about their work every day.

COST AND CAUSES OF STRESS

Job demands grow, work pace accelerates, information explodes, and social connectivity distracts. These environmental stressors can stimulate significant physical and psychological reactions that take a dramatic toll on individuals and employers alike. Researchers at Harvard and Stanford estimate that workplace stress contributes to at least 120,000 deaths each year and accounts for as much as $190 billion in health care costs in the United States. They found that the number of deaths from workplace stress is comparable to the figures for heart disease and accidents and higher than the number for diabetes, Alzheimer’s, or influenza.1

Researchers at Harvard and Stanford estimate that workplace stress contributes to at least 120,000 deaths each year and accounts for as much as $190 billion in health care costs in the United States.

Most company executives implicitly recognize the employee health and economic implications for their businesses and their workforces. Respondents to Towers Watson’s 2013/2014 Staying@Work survey (senior managers in human resources) identified stress as the number one risk to employee health.2 But check with employees about organizational efforts to address stress, and they’ll tell you company actions are often ineffective or nonexistent. Companies commonly institute programs that urge employees to get to the gym, learn to meditate, or take an online resilience course. These programs are often doomed to fail because they do not address the underlying causes of stress, many of which result from tensions within the local work environment. When asked, “What does your office do to help alleviate stress in the workplace,” 66 percent of the employees responding to a Monster.com survey said, “Nothing.”3

Nearly a third of the respondents to our managers and stress survey said they are often bothered by excessive pressure on the job. A look behind this number reveals three principal factors that produce stress and pressure in the work environment. These dominant stress drivers are:

- Mismatch of job demands and resources. Inadequate staffing emerges as the number one workplace stressor. But the underlying concern goes deeper: post-recession workloads have remained burdensome as hiring has lagged production requirements. “Do more with less” has evolved from meme to cliché to cruel joke.

- Rewards not commensurate with effort. Perceptions of stagnant pay levels and microscopic pay increases reflect an abiding skepticism among employees about the relationship between contribution and reward. Towers Watson’s analysis found that only 53 percent of respondents agreed that their managers do a good job of linking pay with performance. Managerial failures to provide highly valued intangible rewards compound the problem. For example, just 49 percent of respondents to our survey said they receive consistent recognition for a job well done.

- Lack of control over the intersection of work and non-work life. Anyone whose job carries an open-ended performance commitment—from individual contributor to CEO—is likely to experience tension between the demands of work and family. As one employee said in a survey of his organization, “Sometimes at the end of the day you have completed three or more work orders and are ready to go home and when you call to get released, you’re sent to another job and end up getting home 7 pm to 8 pm. I have a family (with) whom I enjoy spending time, and usually these late arrivals home hinder that time. I don’t want to feel like all my waking time is spent at work” (confidential client survey, 2014). These factors combine elements that operate at the organization level with manifestations that have roots in the local work environment and in the behaviors of employees’ immediate managers. Company policies that keep wages frozen while productivity pressures rise lie beyond the control of the immediate manager, for example. But many of the psychosocial stressors identified in our analysis derive, directly or indirectly, from the decisions and actions of the supervisors and managers to whom stressed employees report. Anyone who reflects on his or her own work experience can probably remember times when a micromanaging, overbearing, or disengaged boss created a work experience rich with stressors.

Many of the psychosocial stressors identified in our analysis derive, directly or indirectly, from the decisions and actions of the supervisors and managers to whom stressed employees report.

INDIVIDUAL TRAITS HELP DETERMINE HOW PEOPLE COPE WITH STRESS

The effects of stressors result from the interaction of environment with individual characteristics. Such personality traits as hardiness, optimism, hope, and self-esteem increase resilience and coping ability. Also, people who have a strong sense of personal control over their lives suffer less from the effects of workplace stress. Extraverts, who tend to have an elevated sense of personal well-being, also show resistance to stressors.4

On the negative side, people who tend to experience anxiety, depression, and guilt (which social scientists capture with the term neuroticism) display more vulnerability to stress than their more confident, self-assured peers. Type A personality is also a stress magnet. Being a member of a minority community can also heighten workplace stress. In a survey by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, one-fifth of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender respondents said they feel exhausted from expending time and energy hiding their identities.5 A study of workers in the United Kingdom found that black African-Caribbean workers who suffer racial discrimination at work are almost nine times as likely to experience stress as those who perceived no discrimination.6 Women are also more likely to report physical symptoms associated with stress, but they also do better than men at forging social connections that help alleviate the consequences of stressors.7

MANAGERS CAN CREATE A CULTURE OF FULFILLMENT

Organizations are minefields of stressors; human responses to stress are complex and individually idiosyncratic. Consequently, eradicating all stressors from the work environment is impractical. Managers can, however, modify stressors and introduce stress-buffering conditions into the workplace. By doing so, they can transform much of what employees experience as damaging stress (or distress) into a more productive form (referred to as eustress). This transformation can not only reduce the unhealthy effects of stress but also increase employee satisfaction and productivity. We use the term fulfillment for the outcome of positive stress. These are examples of the items that define fulfillment in the 2014 Towers Watson Managers and Stress Survey:

❏ I am doing something I consider really worthwhile on my job.

❏ Over the past month, I felt enthusiastic at work most of the time.

❏ My job provides me with challenges without overwhelming me.

❏ My work gives me a sense of personal accomplishment.8

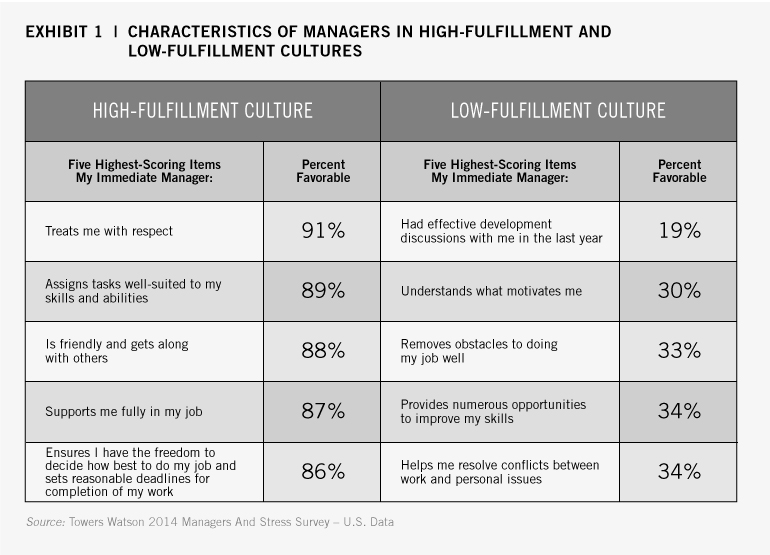

Exhibit 1 shows the five factors most strongly present in high-fulfillment climates and the five biggest deficits in low-fulfillment environments.

In work units where tasks and skills align, where people receive support from and perceive camaraderie with their managers and their peers, and where people have the latitude to control how they go about their work, fulfillment thrives.

Clear patterns appear. In work units where tasks and skills align, where people receive support from and perceive camaraderie with their managers and their peers, and where people have the latitude to control how they go about their work, fulfillment thrives. Where there are deficits of concern about individual development and motivation, where political and logistical obstacles hinder performance, and where conflicts between work and personal life persist, fulfillment suffers.

FOUR MANAGER ACTIONS THAT CAN INCREASE FULFILLMENT

Analysis of these findings, along with data from some two dozen interviews with companies and researchers, led us to identify four manager action areas associated with fulfilling work environments. These four areas set the stage for improved employer and employee performance and enhanced employee health and well-being. When managers build work environments with more fulfillment and less damaging stress, people report experiencing significant reductions in stress-related inhibitors to productivity and health. In our Managers and Stress Survey, people working in low-stress environments said that, compared with people toiling in high-stress workplaces, they are:

❏ 52 percent less likely to say that their health hinders their productivity some of the time or more often;

❏ 6 percent less likely to come to work and underperform because of illness, boredom, or emotional distractions; and

❏ 30 percent less likely to have been absent from work four or more days in the last year.9

By one estimate, unscheduled absence alone costs US employers nearly $4,000 annually per hourly employee, and about $3,000 per year for each salaried employee.10 Reducing the stress- related contribution to these costs alone could save large companies many millions of dollars annually.

Of the four manager action areas, the first two—calibrating work challenge and delivering a return on employees’ investment in work—speak to the fundamental ways managers go about their core responsibilities: getting work done and recognizing the people who do it. The second two areas—generating energy and enabling workplace autonomy— refer to the culture a manager establishes within the team.

1. Calibrating Work Challenge

Calibrating challenge means finding the sweet spot of work requirements. Hitting the ball on the sweet spot of a tennis racquet generates high force with little perceptible vibration. In the workplace, the sweet spot of stress occurs where managers ensure that the right balance of factors comes together to mitigate the stress resulting from misalignment of job demands with individual capabilities and needs.

Consider how differently employees experience work challenges that are:

❏ Consistent with employee abilities (an inspiring but reachable stretch goal) or out of alignment (a goal that is either too easy or impossibly out of reach);

❏ Feasible in the time provided (a trenchant analysis due in a month) or required impossibly quickly (the same analysis expected in two days);

❏ Freely chosen (a project selected by the individual and constructed as an engaging experience) or externally imposed (a difficult task commanded by a micromanaging boss);

❏ Supportive of personal growth (a chance to learn a new skill or perfect an existing one) or a rote task (the same old monthly data-entry routine again);

❏ Associated with an important and potentially gratifying outcome (nailing the critical presentation for a key client) or a routine, trivial one (carrying the reports to the presentation but remaining silent during the session); and

❏ Reinforced by feedback (getting advice from a mentor during the course of the work) or performed in isolation (not learning about success or failure until the end of the effort).

These six factors constitute the sweet spot of stress. Within the high-fulfillment employee group from our managers and stress survey, managers score high on the first two (particularly important) factors: assigning tasks that are well-suited to employee skills and abilities and setting reasonable deadlines for completion of work. Positive stress isn’t just productive—it’s also good for you. Researchers have associated elevated levels of dopamine (the reward related neurotransmitter) and noradrenaline (a hormone that increases heart rate and blood pressure in preparation for action) with positive stress.11 Studies have also shown that people who pursue activities with a high self-determined life purpose exhibit reduced levels of inflammatory indicators.12

Studies have shown that people who pursue activities with a high self-determined life purpose exhibit reduced levels of inflammatory indicators.

Conversely, a poorly calibrated challenge reduces fulfillment and causes frustration. I saw an example when I got to know people in the finance function of a not-for-profit organization. The controller of the organization described how she felt about working one Saturday:

I had to go into the office to create some reports over a weekend for a board meeting on Monday. My boss, the CFO, told me, “No one will look at these, but we promised to do them, so we’re stuck.” I wasn’t happy about going in, but it could have been a lot better. If I could have tried a new approach, if the reports had helped the board make a significant decision, if I had been able to present the analysis and explain what it meant, and if someone had acknowledged that the work was important and well done—but none of that was true. As it was, I just sacrificed my Saturday for nothing” (confidential personal interview with author, October 10, 2014).

Her psychosocial balance sheet was heavily tipped toward the debit side. Perhaps the task could have been eliminated entirely— always a good place to start in reducing excess workload as a stressor. But beyond that, a recalibration of the circumstances— well within the power of her superiors— would have redefined her experience and transformed the stress she experienced. Sometimes, calibrating work challenge means making it explicitly acceptable for people to take time off. Yelp, the fast-growing consumer Internet company, took an extraordinary step to put boundaries around work-time expectations. The head of human resources and the chief operating officer created a video blog to explain the company’s philosophy to managers. They made a few clear but dramatic points: no scheduled meetings on weekends, or time off to make up for any meetings that must occur on Saturday or Sunday; ask people to plan ahead for vacations and then don’t expect them to check in while gone; encourage employees to use holiday time to focus on family; don’t require people come to work sick and jeopardize the health of the team; let people know it’s OK to stay home if a family member is ill. The ultimate message for managers: calibrate work so that people can both hustle on the job and have time off when they need it (personal interview with author, September 17, 2014).

2. Delivering a Return on Investment in Work

In the knowledge-intensive twenty-first century, employees are not an organization’s most important assets. Rather, the intellectual intangibles they own—knowledge, skill, talent, behavior—represent the critical assets. Each person brings a portfolio of this human capital to work every day. Each can invest it as he or she chooses, in a job and an organization with whom one can form a reciprocal contract.

What do employee-investors want from their work? The same thing any investor wants: a maximum return on their investment (call it ROIw, the return on investment in work). ROIw encompasses extrinsic elements like pay, health care, and retirement benefits. It also incorporates an array of intrinsic elements: fulfilling work; opportunities to grow and learn; paths to advancement in the organization; formal and informal recognition for strong contribution; and social connections within the workplace.

Thinking of rewards as return on investment introduces an element often missing in the way organizations conceive of the value proposition they offer employees. That element is fairness.

Thinking of rewards as return on investment introduces an element often missing in the way organizations conceive of the value proposition they offer employees. That element is fairness. A sense of chronic unfair treatment—extended periods of less-than expected pay, inadequate recognition, diminished career opportunities—increases stress and takes a toll on individual well-being.13 One study that looked at coronary heart disease over a five-year period found that people who experience increases in effort reward imbalance had a relative risk two to four-and-a-half times higher than those who were comparatively free of this source of work-related stress.14

Many managers believe their role in generating ROIw stops with administration of pay programs. They couldn’t be more wrong. Our research consistently shows that nonfinancial rewards have far more power to build employee engagement than do dollar-denominated reward elements. Moreover, managers often have substantial latitude in giving nonfinancial recognition for individual and team contribution to success, providing exciting project opportunities, channeling employees into valuable learning programs, and creating on-the-job learning opportunities. Learning and development stands out as an especially important element. It not only fuels engagement but also makes work challenges more appealing and supports effective autonomy. In other words, it has a powerful effect as a stress transformer. Yet, only 40 percent of respondents to our managers and stress survey say their managers provide effective career developmental advice, and barely half (52 percent) agree that their managers provide ample opportunity to develop useful skills. In what emerged as low-fulfillment cultures, these percentages drop into the 30s or lower.15

Some organizations realize this deficit in manager competence and take steps to improve manager performance. For example, Towers Watson’s manager-training programs use specific exercises that help awaken managers to the breadth of control and influence they have over important elements of ROIw. In a session we conducted at a major university, the managers in the training group made lists of reward components in three categories:

- Elements over which they have complete control (interesting project assignments and informal recognition, for instance);

- Elements they influence but don’t fully control (for example, annual pay increases); and

- Elements over which they have no control (the structure of retirement plans, for example).

The managers were surprised to see how many reward elements they either control or influence. The managers went away from the session with a renewed sense of their ability to deliver to people a meaningful return on investment in work.

3. Generating Energy

Even well-calibrated challenges drain an individual’s energy over time. Therefore, managers must provide resources and forms of support that build employees’ productive energy and buffer against the harmful effects of stress. Workplace cultures rich with energy have been linked with heightened regulation of negative emotions, healthy reactivity to stressors, and improved immunological function.16

Energy-generating resources come in two forms. The first category—resources that play an instrumental role in job performance—is basic and familiar. These resources include access to information and tools needed perform key job tasks (for instance, technology for analyzing information).

The second resource type—social and emotional support—has at least as much power as concrete resources to counteract stressors. According to 2014 data from the American Psychological Association, people who say they receive emotional support put their overall stress levels at 4.8 on a 1–10 scale. In comparison, people who say they lack emotional sustenance gave themselves a 6.2 rating.17

Within the workplace, social support includes such factors as coworker camaraderie and teamwork. Emotional support encompasses listening, caring, and commiserating. Managers provide emotional and social support by being friendly, respectful, and available to provide help and encouragement. The managers and stress survey turned up a surprising finding: the two items receiving the highest scores in energy-rich workplaces (“My manager treats me with respect” and “My manager is friendly and gets along well with others”) revealed just how important personal connections are. Humans are social beings, and social contact brings a sense of personal value that increases well-being and provides a buffer against the effects of stressors.

Humans are social beings, and social contact brings a sense of personal value that increases well-being and provides a buffer against the effects of stressors.

Even in the supremely rational world of high-technology engineering, the social aspects of support can be hugely significant. In the words of one executive with experience at a series of technology start-ups:

When engineering management is done right, you’re focusing on three big things. You’re directly supporting the people on your team; you’re managing execution and coordination across teams; and you’re stepping back to observe and evolve the broader organization and its processes as it grows. On the day-to-day front, you want to make sure that everyone is happy, productive, and engaged in their work. This includes meeting with people regularly one-on-one and making the time and space to talk about any smaller issues they have or roadblocks in their way. It may also mean putting everything on pause to take a walk with someone who is having a tough day.”18

An environment characterized by strong social support within the team and from the manager is not only an energy-generating place to work but also a healthy one. In one study, researchers found that people with comparatively high levels of vigor, greater well-being, and a prevailing sense of calm displayed higher resistance to developing colds and reported fewer cold symptoms.19 In another study, researchers drew connections between favorable moods such as joy, interest, and alertness—all manifestations of energy—and lower concentrations of the stress hormone cortisol.20

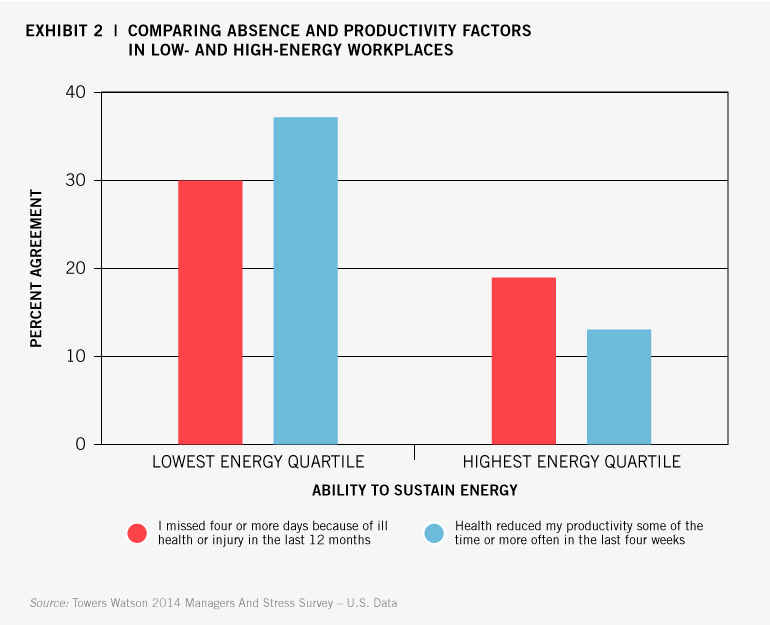

Our analysis showed that working in an environment with ample performance-fueling and stress-buffering energy produces significant benefits for individuals and organizations. As Exhibit 2 illustrates, employees in high-energy workplaces say they take fewer absence days and perceive less effect of ill health on their productivity than their energy-deprived peers.

4. Enabling Workplace Autonomy

For the past several decades, managers have been urged to empower employees. Empowerment refers to the transfer of a quantity of power from manager to employee. It’s a zero sum game; the manager’s power diminishes by the amount given to the employee.

Autonomy, in contrast, means self-rule. It calls on managers to help employees master their jobs and then to grant them self-determination in how they accomplish their work. Autonomy does not mean independence, however, nor does it imply action without mindfulness. People with autonomy can choose to work with others, to sublimate their needs for the good of the whole, to take on unpleasant tasks, or to place themselves under an authority. The key to autonomy is that they do these things willingly and with the full understanding that they could make other choices (and experience the associated risks and consequences, of course).

The managers and stress survey captured autonomy with items like “My manager ensures I have the authority I need to do my job well” and “My manager ensures I have the freedom to decide best how to do my job.” Both of these are among the highest-scoring items in high-fulfillment work cultures.

In its most robust form, workplace autonomy manifests itself in the ability to craft a role with contours that snugly fit an individual’s abilities and aspirations and simultaneously meet the organization’s need for execution of a set of tasks.

In its most robust form, workplace autonomy manifests itself in the ability to craft a role with contours that snugly fit an individual’s abilities and aspirations and simultaneously meet the organization’s need for execution of a set of tasks. Doing this may require flexing the fundamental elements of a role: the what, the where, the when, and even the why of a job. Here are some examples of job sculpting enabled by managers who give competent people autonomy over their work:

❏ Changing the scope of tasks—volunteering to advise the marketing team that has responsibility for promoting the product a group has just developed.

❏ Making an opportunity to innovate—looking for a better way to perform a key process or deliver a customer service.

❏ Taking on additional tasks—stepping up to train new hires on equipment an employee has mastered.

❏ Broadening a personal network—reaching out to people in public relations to get new ideas for internal communications.

❏ Redefining the purpose of a job—refocusing an R&D team member’s role as instrumental to achieving the organization’s future revenue goals, rather than just churning out new product ideas.

❏ Flexing the timing of the job—changing team members’ workday start and finish times to accommodate important non-work aspects of life.

❏ Flexing the location of the job—doing work in the most convenient location rather than being constrained to the work site.

When these opportunities exist, people have the wherewithal to fit together the work and nonwork aspects of their lives into a sustainable whole within which they can thrive.

W. L. Gore & Associates, the well-known manufacturer of Gore-Tex fabrics and many other industrial and consumer products, exemplifies a dedication to worker autonomy. The company website says the organization is “free from traditional bosses and managers” and that “there is no assigned authority.” In this rigorously nonhierarchical company, managers act as “sponsors” who commit to the success of each associate rather than as bosses who direct work. Associates, in turn, are expected to sculpt their jobs, manage their own workloads, and take on challenges that lead to innovation and company success.21

Just about every job has some potential for autonomous worker control over place, time, or tasks. Even many hourly jobs contain elements that can be rearranged to afford employees some flexibility in how they do their work. Hospital custodial employees, for example, can work out ways to trade tasks within a team or to flex their shifts, adding some control and richness to their work experience. In one study of a Midwest hospital where hourly employees enjoyed a degree of autonomy, some members of the cleaning staff went out of their way to become acquainted with patients and families, offering support in small but important ways: a box of tissues here, a glass of water there. One housekeeper reported rearranging pictures on the walls of comatose patients, hoping the change might stimulate them to recover.22

Just about every job has some potential for autonomous worker control over place, time, or tasks. Even many hourly jobs contain elements that can be rearranged to afford employees some flexibility in how they do their work.

UPGRADING MANAGER PERFORMANCE

To master the alchemy of stress transformation, managers must demonstrate compassion— empathy combined with a motivation to deal with stressors that compromise employees’ physical and psychological heath. Managers must also have more than a compassionate disposition, however. They also need a specific set of skills and traits. They must:

❏ Have the ability to observe, understand, and interpret the symptoms and causes of stress;

❏ Understand how to implement actions within the four action areas described above; and

❏ Have access to enterprise resources that support a person-specific response, including workplace options that manager and employee can put into place (for instance, a formal program that encourages workplace flexibility).

Towers Watson works with one major North American bank that took a systematic approach to improving manager performance in these areas. The organization began by analyzing employee opinion survey findings to identify the causes of a subtle but alarming trend toward lower employee engagement scores. Declining employee engagement, the bank knew, is sometimes a leading indicator of emerging workplace stress issues. The company delved deeply into the data, looking for units where employee disability data suggested problems with manager performance. A close look at manager ratings for the best and worst-performing units revealed patterns the organization could address. Armed with an understanding of the specific manager traits and behaviors associated with better and worse employee mental health, the bank created an e-learning program to educate managers in identifying and responding to stress-related behavioral symptoms. The training also instructed managers about when they could take direct action to help an employee deal with a stressful situation and when to refer the employee to a medical expert or other professional practitioner.

The manager roles described here are the hallmarks of a leadership culture that envisions the manager job as central to employee well-being and critical to achieving the economic benefits of a healthy workforce. Such a culture calls for senior executives to value employee health and demonstrate their commitment to improving it, one employee and one manager at a time. We urge executives to keep in mind an idea that came from one of the organizations we interviewed: when employees thrive, so do organizations. But when managers don’t or can’t foster individual fulfillment, neither the individual nor the enterprise prospers fully.

NOTES