Over the past decade, there has been a growing trend among global organizations to treat their employees as internal consumers. The most innovative of these companies have gone a step further by embracing the concept of “consumer-driven HR” — that is, a mindset and an operating philosophy that acknowledge and respond to the increasing variety of work-related choices available to employees. This approach has significant potential to an impact on the design and administration of total rewards programs, thus influencing the work and careers of total rewards professionals around the world.

Characteristics of Consumer-Driven HR

Companies adopting the characteristics of consumer-driven HR recognize that employees today have a broader level of information and choice in many areas, including a greater range of career options, a wider array of employers from which to choose and more flexible programs offered by specific employers (with more features selectable by employees). These expanded choices have in turn made corporate life a more efficient marketplace for its increasingly savvy employee-consumers.

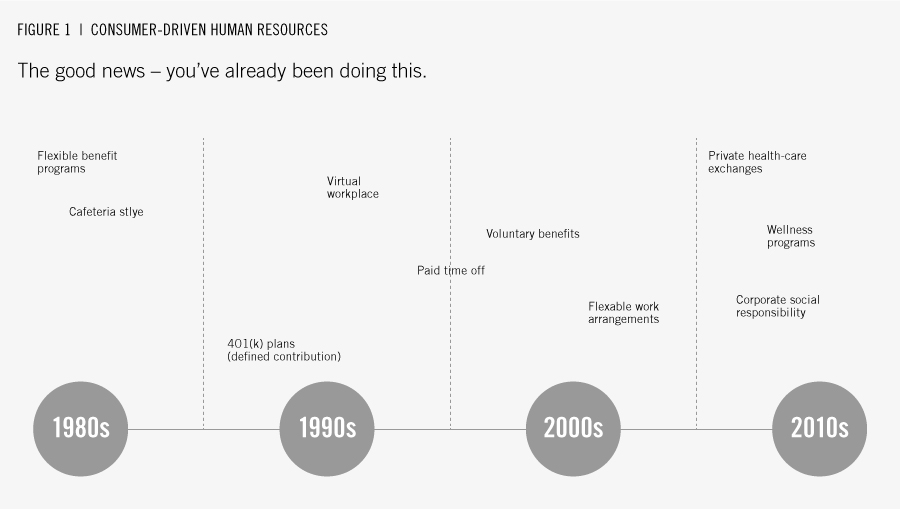

As Figure 1 illustrates, the roots of this shift in program design actually go back to the 1980s, when companies introduced choice-based programs, such as flexible-benefits and cafeteria style plans. The trend continued with the migration from traditional defined benefit pension plans to 401(k) plans that put employees in the driver’s seat in terms of savings amounts, investment decisions and fund disbursement.

… leading companies have turned to consumer marketing theory to gain insights about — and connect with — their current and potential talent.

Today, change continues as private health insurance exchanges provide an alternative to traditional single-carrier plans in the United States. Coupled with the evolving demographics of today’s global workforces and the need for employees to become more accountable for their role and decisions in career and benefit choices, these trends have motivated organizations to tailor elements of the work experience to their increasingly diverse — and well-informed — employee populations.

Today’s employees are more mobile, educated, technologically enabled and short-term-focused than ever. They also have become informed consumers of their organizations’ brands, culture, and compensation, benefits and career development programs. And with the first Generation Z employees entering the workforce, companies can expect that the preferences and expectations of their employee populations will continue to change, becoming more personalized and more sophisticated along the way.

In response to this emerging consumer-employee, leading companies have turned to consumer marketing theory to gain insights about — and connect with — their current and potential talent. Just as companies are using technology and Big Data to direct products and services to ever more carefully targeted segments of customers, organizations are starting to understand the different segments of their varied workforces including what motivates them and what elements of the employee value proposition (EVP) they value most.

Treating Employees as Consumers

The 2014 “Global Workforce Study,” conducted by the authors’ company, reports that 70 percent of employees believe their organization should understand them to the same degree that they are expected to understand external customers. Yet only 43 percent of employees report having an employer that understands them in this way. A central tenet of marketing theory suggests that not all customers want the same things. The corollary is that not all customers are equally important to the company. Both concepts also apply to the market for employees. Companies that take a “consumer-driven HR” approach use consumer marketing principles to define and understand employee groups by what they need and by their contributions to the success of the business. For example, the most innovative companies:

- Segment the employee market. Innovative organizations begin by defining employee segments in ways that extend beyond classic demographic groupings. Effective segmentation criteria leave generous room for creativity in exploring the values, attitudes, preferences and relative contributions of the employee population. Most organizations begin by collecting information from standard demographic and generational categories, but more relevant segmentation variables emerge, including strategically critical roles or locations, actual and potential performance levels, engagement levels, life stage segments and attitudinal categories. These data provide organizations with additional information and insight beyond what can be derived from conventional segmentation approaches.

- Measure how employees value rewards elements. After segmenting the employee population, companies can test rewards elements to determine which have the highest perceived value to particular employee groups. The objective is to understand and define the value proposition with the greatest appeal to each group. Consumer-products companies do the same thing when they conduct sophisticated market research to understand how their target segments will respond to the features and price of a proposed offering. This research can take a number of forms, including focus groups, data mining, employee surveys and tradeoff analysis (which presents employees with scenarios to determine what they view are the most and least valuable components of their rewards package).

- Analyze the financial and behavioral implications of rewards. Once companies understand what employees value (market researchers call these utility preferences), the information can be translated into guidance for determining rewards that the organization can deliver. Program design hinges on the relationship between what employees value (and the resulting behaviors, like commitment and engagement, that these programs encourage) and the cost to provide a specific array of rewards. The ultimate goal is for the company to identify ways to fund more desirable rewards by shifting investment away from less desirable rewards areas (those with lower perceived value relative to cost).

Examples

Earlier this year, a top global employer was considering a move to private health-care exchanges, primarily to reduce costs. It discovered that only about one-third of its U.S. workforce preferred to have a choice of health plan or carrier, and the executive team was concerned that many employees would perceive exchanges as a take-away. The total rewards team recommended that the company conduct a detailed conjoint analysis to determine whether, and to what extent, specific key employee groups in the organization valued health-care choice more than others. The output of the analysis was powerful, showing that several key groups actually favored choice and attached positive perceived value to health-care programs that offered choices over those that did not. These groups included difficult to retain Generation Y employees (73 percent preferring choice), high performers (61 percent), mid-career managers (60 percent) and those in certain key-skill roles (53 percent). For these critical employee segments, a move to exchanges could actually enhance the employee value proposition, increase engagement and save the company millions of dollars in health-care costs.

In another example, a global life sciences company’s tradeoff survey reported that increasing flexible work arrangements would cost the organization nearly nothing financially (and could even save real-estate costs), but would increase employee engagement by 2.1 percentage points. Conversely, reducing the trend of growth in employees’ medical premiums would produce a similar increase in engagement (2.1 points), but with a multimillion-dollar incremental cost.

The Chief Employee Experience Officer

Last year, Scott Sherman, head of human resources of Allergan, observed, “Just as the chief marketing officer has become the chief consumer experience officer, I aspire to become the ‘chief employee experience officer.’ That’s a long way from being a personnel manager.” Sherman is not alone in this view. The evolution of the chief HR officer (CHRO) role from a backroom personnel director to C-suite continues, as does the value these executives contribute to their organizations. (See Figure 2)

While today’s CHRO may have come a long way from the tactical, operationally oriented personnel manager of previous generations, leading heads of human resources are taking another step beyond the strategic, business-focused nature of the modern CHRO role. This new incarnation, the “chief employee experience officer,” acts as a board adviser and futurist focused on differentiating talent (that is, identifying key roles and the employees who excel — or have the potential to excel — in those roles), and helping organizations redefine “employee” as an active value creator rather than simply an asset. Chief employee experience officers envision well-designed programs as a necessary-but-not-sufficient condition for creating a high-performance organization. Their ultimate objective is to weave together a company’s brand, programs, culture, vision, values and environment to create a differentiated experience for its employees.

A great CHRO will say, “I direct programs to balance the needs of employees, the company and shareholders.” But a great chief employee experience officer will say, “I create an employee experience that unleashes the potential of our talent to create incremental value for our customers and shareholders. And I do this in a way that pulls the highest possible value out of every dollar my organization invests in employees and their work environment.”

Impact on Total Rewards

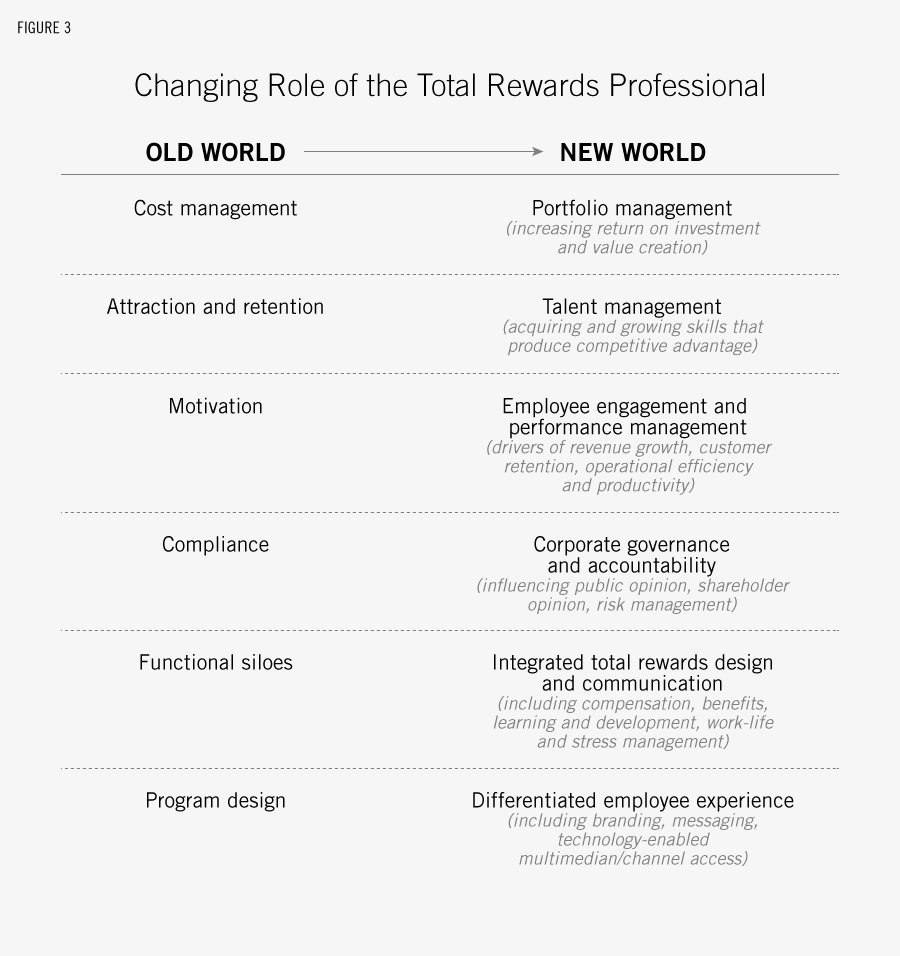

There is considerable good news here for total rewards professionals. First, most have been working in organizations that long ago stopped looking at specific rewards programs in a vacuum. The siloes separating compensation, benefits, learning and development, and work-life are far less pronounced today than they were in the past. Progressive organizations routinely look at the entire total rewards picture when designing programs — regardless of what part of the HR organization has responsibility for each component. They share the total value of programs (the “total deal”) with employees through comprehensive rewards statements and other communications designed to emphasize that “rewards” means much more than just pay. Second, most organizations have a history of offering programs that involve employee choice. Whether it is a flexible benefit program, a 401(k) or 403(b) plan, a PTO program, a spectrum of alternative work arrangements, or a private health-care exchange, virtually every employer today has at least some experience with employees making selections, exhibiting choice and acting as informed consumers. The next step for total rewards becomes moving past program design to create a truly integrated and differentiated experience for employees.

The siloes separating compensation, benefits, learning and development, and work-life are far less pronounced today than they were in the past.

A quick scan of the public websites of leading organizations provides a vision for the future in terms of differentiated experience. At the Procter & Gamble career site, for example, potential candidates learn that P&G “hires the person rather than the position.” The site is video intense — viewers can see vignettes of employees in Asia, Europe and the Americas talking informally about their jobs. And they also can watch a humorous four-minute clip of a potential hiree being interviewed by a bottle of liquid Tide. It feels more like a consumer product experience than a classic job search moment, which is the whole point.

Google expands its “Do cool things that matter” brand slogan to include three categories (“Build cool stuff; sell cool stuff; do cool stuff”) that explain various teams and roles to current and potential talent. This is how the company appeals to employees and recruits in a more interesting way — and in a manner more aligned with the Google culture — than simply using such conventional department names as engineering, sales, customer support, finance and administration.

Kellogg’s applies its “Grow with us” brand to its employee experience. IBM says, “Help us build a smarter planet.” JPMorgan Chase says, “Let’s build our legacy together.” Each of these organizations then connects its programs to the intended (and promised) employee experience. Well-designed, market-competitive, financially sound programs remain at the core in each case, but leading total rewards teams take the next step to connect them in an integrated and comprehensive manner, just as their counterparts in marketing do for the external consumer experience.

Impact on the Total Rewards Professional

Given these trends, today’s total rewards professionals are well positioned to refocus on optimizing the value of the employee experience produced by their organizations’ investment in a total rewards portfolio. They may ask their CEO: “How often do you spend $3 billion to develop a product offering without first finding out whether it will sell?” The response is most likely, “You know darn well that if I did that too often, I wouldn’t stay in this chair long.” Yet every year the typical global organization with 20,000 employees invests approximately $3 billion in employee programs that include salaries and bonuses, stock grants, health-care and retirement benefits, training and paid time off. Total rewards professionals with a focus on their employee-consumers can help extract the highest possible value from this investment.

… virtually every employer today has at least some experience with employees making selections, exhibiting choice and acting as informed consumers.

A New Way to Go

Organizations that embrace consumer-driven HR have learned that by understanding and acting on employee needs and preferences, they are more likely to have motivated and committed workforces, even with total rewards budgets that are no greater in aggregate than the investments of their peers. Their employees will be more engaged, serve customers better, innovate more frequently and consistently, and protect company assets more conscientiously. Experience with organizations that have performed the return on investment analysis demonstrates that superior financial results become part of the equation as well.