Designing total rewards based on employee preferences can mean a more highly engaged workforce … and a better return on total rewards investment.

In their 1998 book “Work & Rewards in the Virtual Workplace: A New Deal for Organizations and Employees,” Dr. N. Fredric Crandall and the late Dr. Marc J. Wallace Jr. painted a 21st-century vision that focused on a “new deal” to replace the traditional work and rewards arrangements offered by most organizations.

Today, many of the predictions of the book — for example, the convergence of economic and technological forces to create a new level of business competition — have come true, and a new social contract has emerged between companies and their employees.

… modern organizations have learned that highly skilled contributors actually have myriad employment opportunities, even in the most dire economic environments.

This new contract has become familiar: replacement of the promise of pay progression plus lifetime employment and economic security with an agreement to provide competitive market pay plus skill and experience development that enables future employability.

Now that organizations have more than a decade of experience operating in this millennium, many have come to terms with the reality of this new social contract for those on both sides of the table:

- The view of employers to their employees is: “We will employ you as long as you are adding value commensurate with your costs.”

- In return, employees offer back: “We will work here as long as the value of our rewards is commensurate with our contributions.”

This new social contract would appear to have transferred power to employers, but modern organizations have learned that highly skilled contributors actually have myriad employment opportunities, even in the most dire economic environments. And they are not burdened by the constraints of loyalty or mutual long-term obligation.

We now know that those with the most valuable skills anticipate changing jobs even more frequently than did their Baby Boomer parents. These valuable employees expect that, at some point, their current companies may no longer need them (perhaps because the job or organization will cease to exist in its current form). They learned long ago that they are responsible for their own career development and their own long-term economic security. They also have been taught that there is more to life than work, that they no longer necessarily need to be tied to a corporation to earn a living and that they can shift to new geographies or even different sectors to find opportunities when their current gigs go stale or go away.

These factors have transformed this population of marketable employees from informed job seekers into astute consumers of total rewards and broader employee value propositions. The most visionary organizations have realized this and have begun to treat employees not just as workers, but rather as consumers … of their brand, mission, culture, leadership style, organizational offering, career development opportunities, work environment, and, yes, their total rewards programs.

Yet, many C-suite executives reject this perspective, believing that such notions lead only to higher rewards costs, more entitlement and lower productivity. To the contrary, however, research supports that organizations treating their employees as smart consumers actually achieve lower rewards costs, higher engagement, higher retention, greater productivity and, ultimately, better financial performance.

The recent “2012-2013 Global Talent Management & Rewards Study” by WorldatWork and Towers Watson revealed that companies that have adopted an integrated approach to total rewards strategy, design and delivery decisions — supported by an overarching employee value proposition — are five times more likely than the average company to report their employees are highly engaged and twice as likely to achieve financial performance significantly above their peers.

How is this possible?

Segmenting Your Employee Market

A central tenet of marketing theory says that not all customers want the same things. The corollary is that not all customers are created equal in their importance to the company. It turns out that both concepts apply to the market for employees.

Today’s most effective organizations use consumer marketing principles to define and understand employee groups along dimensions that reflect not only their needs and wants but their contributions to the success of the business.

These organizations begin by defining the most important market segments within the employee population. Effective segmentation criteria leave generous room for creativity in exploring the values, attitudes and preferences of the employee population. Some begin with standard demographic and generational categories. More specific segmentation variables might include strategically critical roles or locations, performance or potential levels, engagement levels, life stage segments and attitudinal categories.

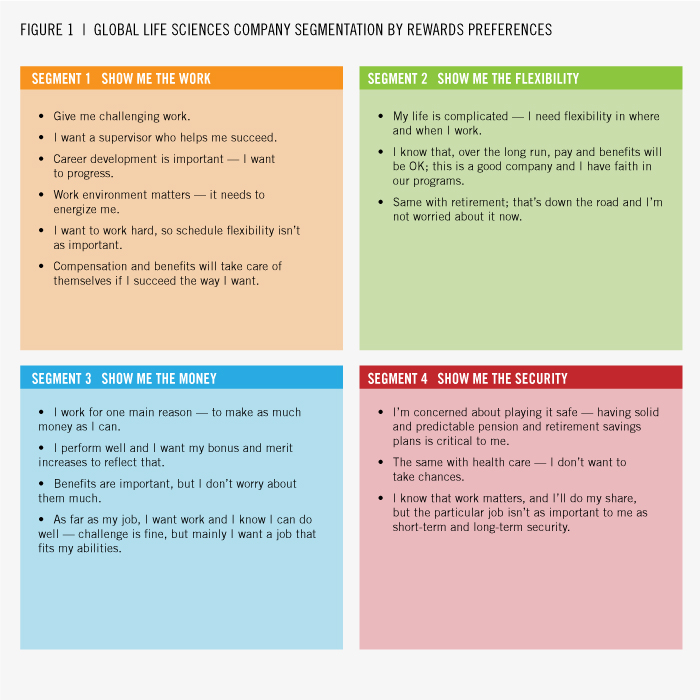

Along these latter lines, a global life sciences company wanted to understand how different parts of its employee population valued particular elements of the organization’s existing total rewards portfolio. The analysis did not stop with conventional demographic segmentation. The team learned that rewards preferences tended to vary surprisingly little across the generational demographic clusters. More meaningful was a set of four employee groups defined by rewards preferences rather than other traits. The four segments, with summaries of their rewards preferences, are shown in Figure 1.

Segmentation according to these factors gave the organization additional information and insight beyond what it could have derived from conventional segmentation. The themes sharpened the messages aimed at employee segments, enabling program designers to invest in programs that met employee needs and divest from programs that did not. The findings also enabled communicators to speak in terms that addressed what mattered to specific employee groups.

Employees’ perceptions of value tend to increase when they receive clear messages that speak directly to their interests, and segment definitions can take on an even more individualized and creative feel through the creation of personas that personalize each segment.

Measuring How Employees Value Rewards Elements

After segmenting the employee population, companies must next measure preferences, in this case testing rewards elements to determine which have the highest perceived value to particular employee segments. The objective is to understand and define the value proposition that carries the greatest appeal to each group. Consumer-products companies do the same thing when they conduct sophisticated market research to understand how their target segments will respond to the features and price of a proposed offering.

This research can take a number of forms, including focus groups, data mining, employee surveys and trade-off analysis (which presents employees with scenarios to determine what they view are the most and least valuable components of their rewards package).

As one example, in its segmentation and preference analysis research, the global life sciences company used trade-off analysis to discover that increasing flexible work arrangements would cost the organization nearly nothing financially but would increase employee engagement by 2.1 percentage points. Conversely, reducing the trend of growth in employees’ medical premiums would produce a similar increase in engagement (2.1 points), but with a multimillion-dollar incremental cost. This information proved invaluable to decision makers and made the choice obvious.

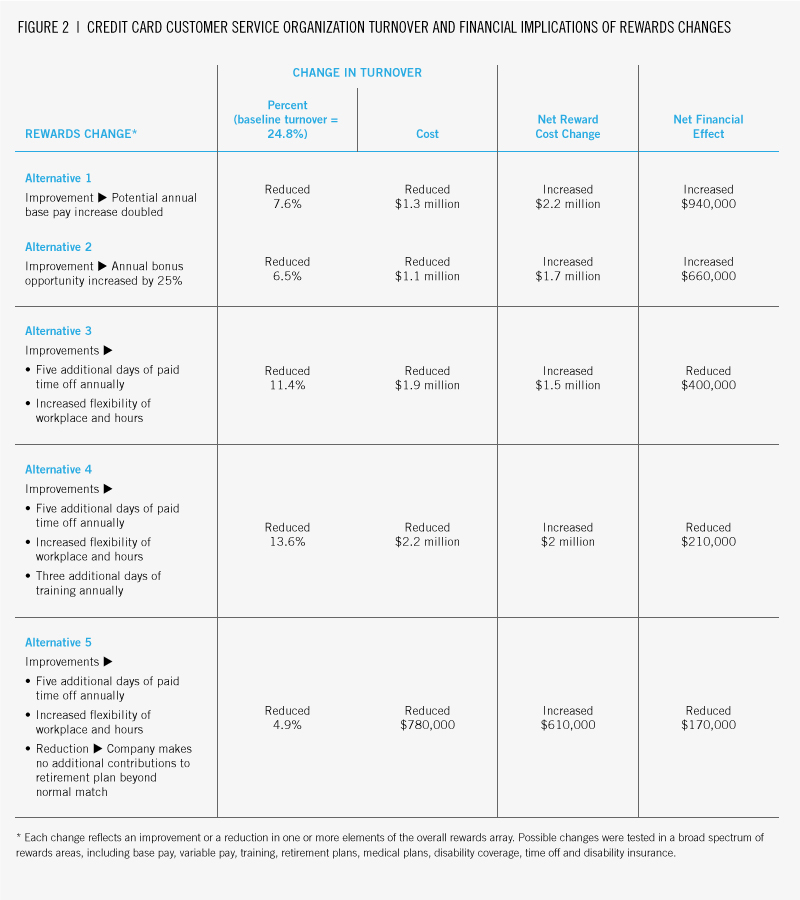

A credit card customer service organization also employed the trade-off analysis approach, focusing specifically on the high-turnover customer service population, a segment critical to the company’s strategic success. By understanding what aspects of the rewards portfolio most directly influence the decision to stay with the organization, the company hoped to tailor rewards to reduce the cost of losing experienced, productive employees.

The company crafted a survey that asked employees to review an array of additions and reductions to their current rewards portfolio and provide the opportunity to indicate how they valued specific rewards elements.

The survey tool provided a broad spectrum of rewards elements within which employees could make dynamic trade-offs that were based on previous responses. Their rewards choices included foundational and performance-based compensation (base pay increases and bonus opportunity) and benefits (retirement plan contributions and medical coverage costs, for example) as well as career and environmental rewards, such as training and flexible work arrangements.

Analyzing the Financial Implications of Rewards

Once employees told the company what they valued, these insights provided the information required to translate that data into rewards the organization can deliver (market researchers would call these utility preferences). The final program assessment hinged on the relationship between what employees value (and their associated behaviors) and the cost to provide any specific array of rewards.

To accomplish this, the credit card customer service organization supplemented the findings on employees’ reward valuations with two other critical pieces of data: the cost to deliver each reward component tested, and the financial implications of changes in employee behavior associated with different rewards combinations. (See Figure 2.)

Each alternative tells a story of trade-offs. For example, in Alternative 1, the data suggest that turnover would decrease if pay was raised, but the salary cost increase would exceed the savings from greater retention by more than $900,000 annually.

The analysis ultimately enabled the company to look for ways to fund more desirable rewards by shifting funding away from less desirable rewards areas (with lower perceived value for their cost) — in this case, the investment in a relatively rich defined contribution retirement plan, which the often-younger call center population did not value as much as other programs.

Conclusion

Organizations have come a long way during the past 15 years in understanding their workforces and creating more meaningful and differentiated total rewards programs. The most astute borrow methodologies from marketing and finance to design rewards programs that meet the needs of key employee segments through prudent investment of the organization’s rewards dollars. The next step for most is to follow the lead of other consumer-driven organizations to optimize the stickiness and long-term engagement of their most valuable (or simply hard-to-find or -retain) employee segments. The goal is to create a win-win-win among employee preference, economic cost and company performance.